How Reliable is the Traditional Scottish Naming Pattern?

How much faith should I put in the traditional Scottish naming pattern as a predictor of the names of the parents’ parents? I am asked this question frequently. Many genealogists researching Scottish ancestors are aware of the traditional naming pattern and thus either jump to conclusions, or are afraid of jumping to conclusions, as to the names of the parents of their ancestor.

So how much faith should you put in the traditional naming pattern? How reliable is it?

The Traditional Scottish Naming Pattern for Children

For those who are unfamiliar with the traditional naming pattern, let me start with a short explanation of it. (If you’re already familiar with it, please feel free to skip this section.)

It was customary for parents in Scotland to name their children after certain relatives in a customary pattern:

Sons

- First son is named after the father’s father.

- Second son is named after the mother’s father.

- Third son is named after the father.

Daughters

- First daughter is named after the mother’s mother.

- Second daughter is named after the father’s mother.

- Third daughter is named after the mother.

Subsequent children could be named anything, but were frequently named after other important family members, like siblings or aunts and uncles.

Post-Emigration Use of the Traditional Naming Pattern

When people emigrate their memory of the customs of their homeland is frozen at the moment of emigration. Whereas, customs and traditions may change and evolve back home, they often remain rigidly adhered to for far longer in the new land. This is why you see way more people wearing kilts in North America than in Scotland.

So we find the naming custom was often religiously adhered to among emigrant Scots in Northern Ireland, Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Jamaica, India, and other countries where Scots immigrated and settled.

Variations of the Traditional Naming Pattern

Father and son have the same name

The pattern gets complicated when names are repeated. For example: If Robert Stewart, son of Robert Stewart, has a child, his firstborn son would be named after his father, Robert. Thus, the first and third slots in the naming pattern would be combined. Robert would name his second son after his wife’s father. And he would be free to name his third son anything.

Grandparents have the same name

Similarly, if Robert’s father was named Duncan and his wife’s father was named Duncan, then the first and second slots would be combined, so his first son would be named Duncan and his second son would be named Robert, and his third son could be named anything.

If Robert’s father and his wife’s father were both named Robert, then all three slots would be combined and Robert would name his first son, Robert, and his subsequent sons could be named anything.

The exact same variations apply for daughters.

Aside: Nicknames

You can see that this custom would lead to certain forenames being used over and over again in the same family. Pretty soon you have a whole lot of people with the same name. How do you differentiate them? Well, this is why nicknames became such a big custom in Scotland. If you have three Roberts in the family, you would give each a nickname, like “Young Rob” or “Black Rob” (for his hair colour), or “Big Rob.”

How Does the Traditional Naming Pattern Help Genealogists?

One of the wonderful consequences of this tradition, is that if you can confidently identify all the children of a certain family, then you can reasonably predict what the names of the four grandparents likely were. This makes finding the parents’ birth records a whole lot easier!

For example: If you’re researching the family of John and Catherine and their children are:

- Duncan (named after father’s father)

- Agnes (named after mother’s mother)

- James (named after mother’s father)

- Margaret (named after father’s mother)

- John (named after father)

- Catherine (named after mother)

Then you can reasonably predict that John’s parents‘ names are probably Duncan and Margaret, and Catherine’s parents‘ names are probably James and Agnes. So when you go searching through the parish records for their births and find records that match those names, you can be reasonably confident that you’ve probably found the correct births.

Whereas if you were searching for an English family with the same names, you would have no way of predicting the names of the parents’ parents.

What Do You Mean That It’s Only “Probably” Helpful?

You’ll note that I said, ” you can be reasonably confident that you’ve probably found the correct births.”

Probably? What do you mean “probably?” This is the challenge. The custom was not adhered to 100% of the time. There were exceptions where the children’s names do not match the grandparents in the traditional manner. (Or they appear not to match!)

So, when you come across a new family, how confident can you be in using the names of their children to predict the names of the grandparents? Well, that depends on a lot of things.

Regional Adherence to the Traditional Naming Pattern

Adherence to the custom varied regionally. Some areas followed it strictly, while others followed it loosely. In the latter cases you’ll find exceptions to the custom to be more common.

I’m not enough of an expert on all areas of Scotland to comment on where it was followed strictly and where it was not. However, I can tell you that after a quarter of a century researching families in southwest Perthshire, it was fairly strictly followed in that region. Thus, in southwest Perthshire, where the Stewarts of Balquhidder primarily resided (including the parishes of Balquhidder, Comrie, Callander, Kilmadock, Kincardine-by-Doune, Port of Menteith, and Aberfoyle), you can consider the pattern to be reasonably reliable in predicting the names of the parents’ parents.

In southwest Perthshire (including the parishes of Balquhidder, Comrie, Callander, Kilmadock, Kincardine-by-Doune, Port of Menteith, and Aberfoyle), you can consider the pattern to be reasonably reliable in predicting the names of the parents’ parents.

However, even in an area of fairly strict adherence, there were still exceptions.

When the Names are Misleading

Research Confounds and Exceptions to the Traditional Naming Pattern

Prior Marriages

The most common reason for a break in the naming pattern is a prior marriage that is unknown to the researcher. If a parent was married more than once and they fulfilled part of the naming custom with the children of their first marriage then they would continue the tradition with their second family; they would not start over again.

Say, Catherine, daughter of Isabel, married James. They had one daughter, whom they named Isabel after the mother’s mother. But then James died prematurely. Catherine married secondly to Robert, whose mother’s name was Ann. Robert and Catherine would name their first daughter Ann, after the father’s mother, not Isabel, after the mother’s mother, because she already has a daughter named Isabel.

That becomes a problem for the researcher if you don’t know that Catherine had a daughter from a previous marriage. If you only know the names of the children from her second marriage to Robert, then you might mistakenly assume that Catherine’s mother’s name was Ann, just like Robert’s mother.

If this family lived during the census era then you might be lucky enough to find an early census with Catherine’s daughter, Isabel, from her first marriage, living with Robert and Catherine. But what if they lived before the census era? Or what if Isabel died young, before the next census was taken? In these cases you might never know there was a daughter from a prior marriage. In fact, the baptism record for the earlier daughter may be staring you in the face and you might have no way of knowing that the Catherine who married James is the same Catherine who later married Robert.

Missing Birth/Baptism Records

The next most common confound for researchers is missing records. For a variety of reasons, not all children’s baptisms were recorded in the local parish register. We’ve found many examples of families where we know children exist, but there is no record of their birth/baptism. Even if the baptism was recorded, the Old Parish Register may be damaged or faded so badly that that record is no longer legible so it does not appear in the index of your favourite online search site.

For example:

Robert and Catherine were married in 1767. Their first recorded child, Duncan, was born in 1772. It was highly unusual for a couple to wait that long to have children in that era.

Is Duncan actually their first born? Did they have a hard time conceiving and it took them five years? Or was there another child born between 1767-1772 for whom the record hasn’t survived, or never existed?

Let’s assume there is an earlier unknown child. Was it a son or a daughter? That’s going to make a huge difference when that child either bears the name of Robert’s father or Catherine’s mother. And we have no way of knowing which!

The same issue holds true for any gap in the birth order of the children, sons or daughters.

Prematurely Deceased Children

In an era of high child mortality, it was not uncommon for children to die young. If that child was one of the first three, thus fulfilling one of the customary naming slots, then the parents would often (but not always) reuse that deceased child’s name with the next child to be born. This preserves adherence to the the custom, but screws up the order of the names of the kids.

If you know about the existence of the earlier same-named child, that’s fine. But, if you don’t know about the earlier child, then it can mess up your interpretation of the naming pattern.

Third Child Humility?

Even in an area with high adherence to the custom, like southwestern Perthshire, it was still not evenly adhered to for all three children. A common variant in the pattern was to follow the custom for the first two slots only but not name the third child after their same-sex parent. Why? I have no idea. Maybe it was some form of humility with the parent not wanting to name their third-born after themselves? Maybe they felt the name was already over used and they’d run out of nicknames? Who knows? But, what I can say, is that it wasn’t uncommon to simply ignore the custom for the third child.

But that’s not a problem, since it’s the first two children whose names are predictive of the grandparents’ names! Right? Wrong.

The problem is that when you come across a family where the third child doesn’t match their same-sex parent, you have no way of knowing for sure if they broke with the custom just for the third child only, or for more, or for all of them.

Before/After the Traditional Naming Pattern Era

The tradition began to fall out of fashion in the late 1800s in Scotland. The later you get into the 1800s and beyond, the less reliable it is. Some families held fast to the tradition, some shed it. As noted above, they were most likely to shed the custom for the third child before ceasing the custom for the earlier children.

In the parishes of southwest Perthshire, where my familiarity lies, the custom was most popular from the 1400s to the late1800s. Earlier or later than that, it may have diminished reliability.

Aristocratic Families

If you’re dealing with a family who had money, whether truly aristocratic, or merely aristocratic in their own minds, they were less likely to adhere to the custom than common families, They were more likely to choose any names they wanted, regardless of pattern.

Who Knows?

And, finally, there are some families that we know of who did not follow the tradition and we have no idea why. They may have had a personal reason to break from the tradition and honour a different family member out of sync. They may have been rebels who thumbed their nose at the tradition. They may not have considered the tradition that important. Unfortunately, they didn’t leave a written record of their reasons, so we don’t know why they didn’t follow the tradition.

Where Does That Leave Me?

If you’re dealing with a family from southwest Perthshire, you can place a high value on the predictability of the naming custom. However, for all the reasons identified above, you can never assume that it’s always applicable. I would estimate that about 20% of our families fall under one of the exceptions above.

Therefore, as a researcher, you can never rely on the naming pattern alone. You always need at least one additional piece of corroborating evidence before you can conclude that any given relationship is “confirmed.”

As a researcher, you can never rely on the naming pattern alone. You always need at least one additional piece of corroborating evidence before you can conclude that any given relationship is “confirmed.”

Gordon MacGregor (Professional Scottish Genealogist) Responds

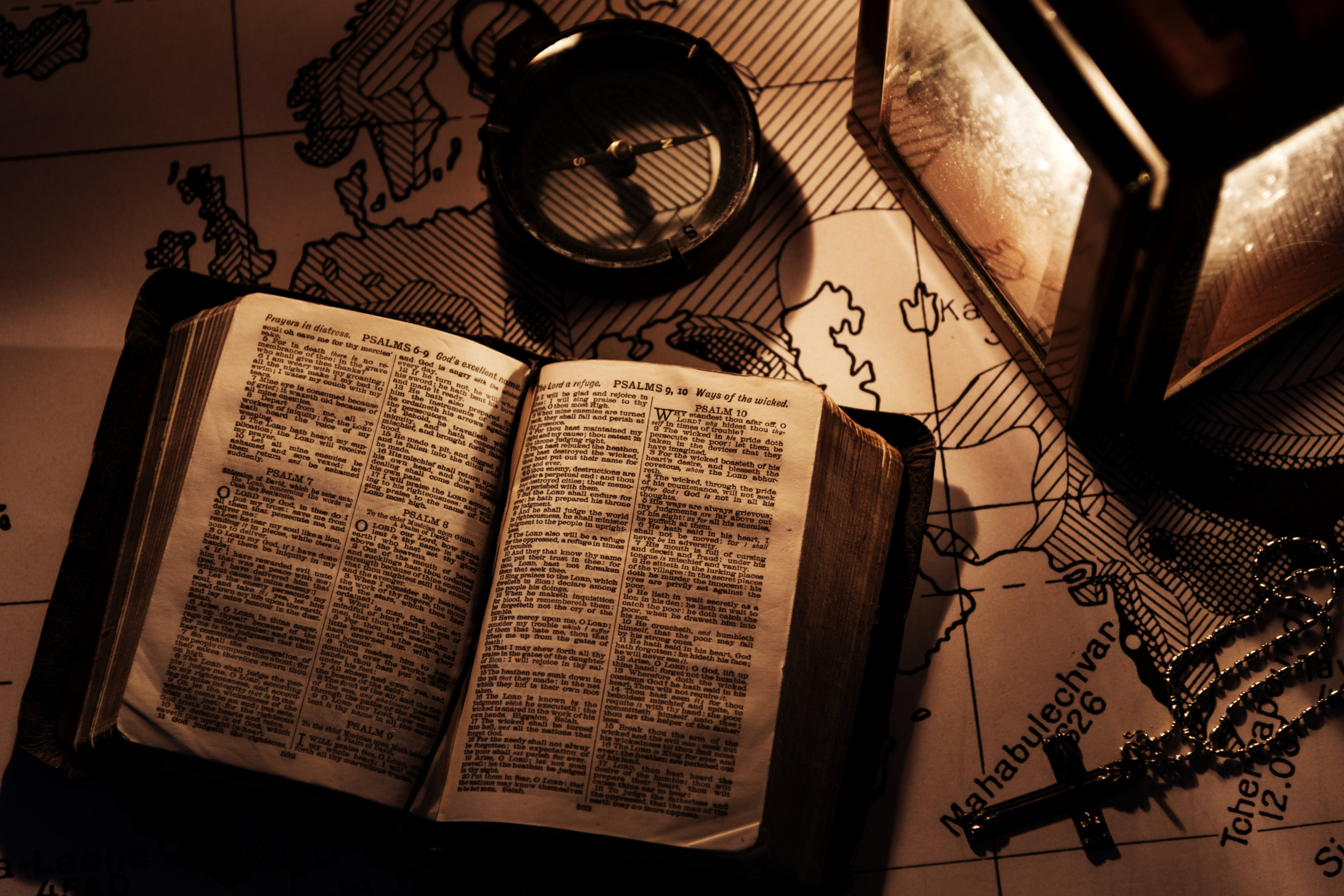

Gordon MacGregor, author of the monumental Red Book of Scotland had this to say on the subject:

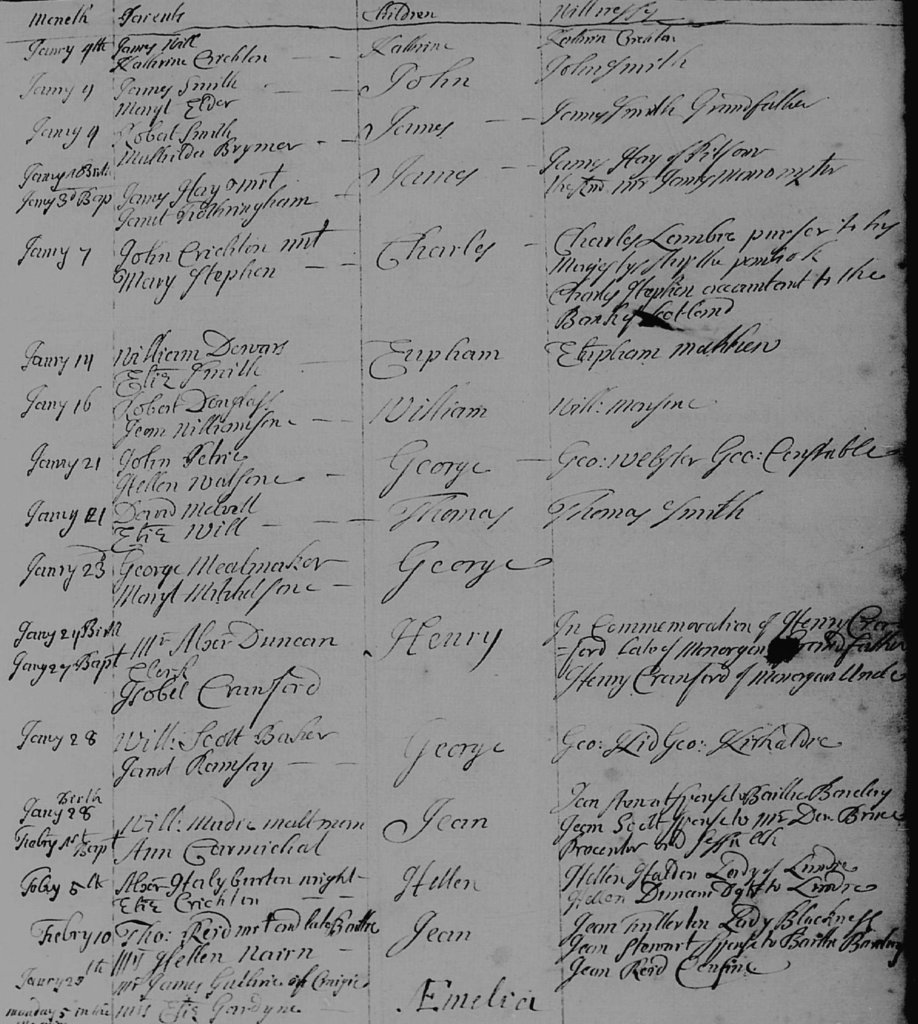

This aspect of research alone would fill a reasonable size book. This single page from the Dundee OPR (below) is a good example of the complexity of the “naming system” within the various orders of society.

- The third entry down states the child to be named after its grandfather;

- in the fourth entry, James Hay of Pitfour is a second cousin of the father of the child;

- in the eleventh entry, the son of Mr Alexander Duncan, (grandson of Alexander Duncan, 1st of Lundie), is stated to be named after both it’s maternal grandfather and uncle,

- and in the second last entry the child, Jean, is named after Jean Fullerton, Jean Stewart and Jean Reid “cousin”.

In Dundee and other OPRs, the terms “namefather” and “namemother” regularly appear, however, such persons need not have been closely related, simply close acquaintances.

See also entries 6-9 which is for persons of that “lower order”. In each the witness bears the same forename as the child and, therefore, is the “nameperson” however that person’s surname does not correspond to that of either the father or mother of the child.

It’s an interesting study but, personally, from what I’ve viewed, I think it’s a little more convoluted and erratic than commonly thought.

0 Comments