The Stewarts of Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland

The Stewarts of Ardvorlich established themselves at Ardvorlich on the south shore of Loch Earn, straddling the parishes of Balquhidder to the west and Comrie to the east, in Perthshire, Scotland. They were a notorious clan whose early exploits were fictionalized by Sir Walter Scott in his book, A Legend of Montrose. They were involved in the proscriptions against Clan Gregor which led to all of the MacGregor name being mercilessly hunted. They were involved in brazen cattle raids, murder, and magic. They had dealings with the notorious Rob Roy MacGregor.

The Stewarts of Ardvorlich still occupy the same property today as their earliest ancestor, Alexander Stewart, 1st Ardvorlich, did over 400 years ago.

Ancestors of the Stewarts of Ardvorlich

The Stewarts of Ardvorlich are the senior branch of Clan Stewart of Balquhidder. Their ancestors can be found on our Stewarts of Baldorran and Balquhidder page.

“Our subject leads us to talk of deadly feuds…”

— Sir Walter Scott, A Legend of Montrose

Sources

In our research, we cite many documentary sources. Some of the most common ones that you will find referenced and abbreviated in our notes include:

- Duncan Stewart (1739). A Short Historical and Genealogical Account of the Surname Stewart…. (It’s actual title is much longer), by Rev. Duncan Stewart, M.A., 1st of Strathgarry and Innerhadden, son of Donald Stewart, 5th of Invernahyle, published in 1739. Public domain.

- Stewarts of the South. A large collection of letters written circa 1818-1820 by an agent of Maj. Gen. David Stewart of Garth, comprising a near complete inventory of all Stewart families living in southern Perthshire, including all branches of the Stewarts of Balquhidder.

- MacGregor, Gordon, The Red Book of Scotland. 2020 (http://redbookofscotland.co.uk/, used with permission). Gordon MacGregor is one of Scotland’s premier professional family history researchers who has conducted commissioned research on behalf of the Lord Lyon Court. He has produced a nine volume encyclopedic collection of the genealogies of all of Scotland’s landed families with meticulous primary source references. Gordon has worked privately with our research team for over 20 years.

- [Parish Name] OPR. This refers to various Old Parish Registers.

- For a full list of sources, click here.

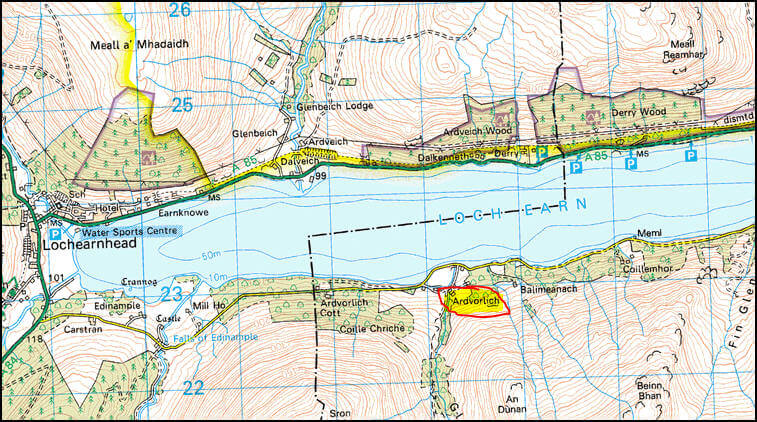

Ardvorlich

Ardvorlich is located roughly midway along the south shore of Loch Earn (“The Lake of the Irish”) in Perthshire, Scotland (see map below). It is located at the west end of the parish of Comrie, but it closely borders with the neighbouring parish of Balquhidder. The current laird of Ardvorlich is Alexander (Sandy) Stewart, 15th of Ardvorlich. Ardvorlich, in Gaelic, is Ard Mhor an t-Sluic, which means “the high lands (or shielings) of the great hollow”. Ardvorlich is located at the foot of Ben Vorlich (“the mountain of the great hollow”).

Loch Earn, ca 1860

Loch Earn, ca 1860 viewed from the west with Edinample Castle on the right and Ardvorlich House just beyond.

Ben Vorlich

Ben Vorlich with Ardvorlich in the foreground, viewed from Dalveich. (Photo by Gordon MacGregor)

Ardvorlich House

Ardvorlich House © Copyright Kevin Rae and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Summer shielings above Ardvorlich

Ruins of an old cottage in the summer shielings lands in the hills above Ardvorlich. Photo by InJacobiteFootsteps.

Near Lochan na Mna view towards Glen Artney

View towards Glen Artney where John Drummond of Drummonerinoch was murdered. Located near Lochan na Mna where James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich was born. Photo by InJacobiteFootsteps.

Lochan na Mna with Ben Vorlich in the background

Lochan na Mna with snow-capped Ben Vorlich in the background. This is where James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich, was born. Photo by InJacobiteFootsteps.

Lochan na Mna Lady’s Loch

Lochan na Mna (“The Lady’s Loch”) where Margaret Drummond of Drummonderinoch, wife of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Ardvorlich, gave birth all alone to James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich. Photo by InJacobiteFootsteps

Partway up Ben Vorlich

Pausing partway up from Ardvorlich to the peak of Ben Vorlich. Photo by InJacobiteFootsteps.

View of Ardvorlich with Loch Earn in the background

A view of Ardvorlich House in the distance with Loch Earn in the background. Loch Earn is so still and clear that it is difficult to tell where the trees on the hillside end and their reflection in the water begins. Photo by InJacobiteFootsteps.

Cadet Branches

The following cadet branch families descend from the Stewarts of Ardvorlich.

Descendant Lines

The following cadet lines descend from the this main branch of the Stewarts of Ardvorlich, below:

Dundurn Chapel

Burial Ground for the Stewarts of Ardvorlich

Just east of Loch Earn is the mediaeval chapel of Dundurn. Dundurn derives from the Gaelic dun dórn, which means “(hill) fort of the fist.” So-named because it was once the location of an early Pictish hill-fort or castle and the hill is shaped like a fist. Dundurn was the capital of the ancient Pictish Kingdom of Fortren.

This Pre-Reformation chapel was dedicated to St. Fillan and became disused after the Reformation. It is now a ruin. The chapel burial grounds are reserved for members of the family of the Stewarts of Ardvorlich. The interior of the chapel is reserved for the burials of the early clan chiefs.

Stewarts of Ardvorlich gravestones in Dundurn Chapel – Photo by Ryk Brown, 2005.

Ardvorlich Gravestones

The Ardvorlich gravestones in Dundurn Chapel are inscribed as follows:

This chapel, dedicated in early times to St. Fillan the Leper, has been since 1586, the burial place of the sept or clan of Stewart of Ardvorlich. At the east end lie the bodies of the following chiefs of that race:

- Alexander Stewart (1st) of Ardvorlich and wife Margaret Drummond (of) Drummonderinoch 1618;

- Major James Stewart (2nd) of Ardvorlich and wife Barbara Murray (of) Buchanty 1662;

- Robert Stewart (3rd) of Ardvorlich and wife Jean Drummond, Comrie, 1680;

- James Stewart (4th) of Ardvorlich and wife Elizabeth Buchanan of that Ilk, 1698;

- (Robert Stewart, 5th of Ardvorlich is noticeably absent from the list.)

- Robert Stewart (6th) of Ardvorlich, died unmarried, 1760;

- Robert Stewart (7th) of Ardvorlich and wife Margaret Stewart of Annat, 1760;

- William Stewart (8th) of Ardvorlich 1838 and his wife Helen Maxtone (of) Cultoquhey, 1853;

- Robert Stewart (9th) of Ardvorlich died unmarried 1854;

- Col. Robert Stewart of the Bengal Staff Corps, 10th of Ardvorlich, 6 JUN 1882, age 52; daughter Charlotte 13 APR 1918, age 55.

- Also of the family James STEWART (1800-1810), Anthony STEWART, student of medicine, 1807-1827, Marjory STEWART of Ardvorlich Cottage, 1805-1878, Georgina Marjory STEWART, born 1871 and died at Strathyre 1873, William Charles Robert STEWART born 1861, killed at Ardvorlich by accident 1875.

Dundurn Chapel

Dundurn Chapel (located in a tree lot not far from the base of Dundurn Hill.) Photo by Ryk Brown, ©2005 Stewarts of Balquhidder Research Group

Dundurn

Dundurn “Hill fort of a Fist” (viewed from beside the chapel) Ryk Brown, ©2005 Stewarts of Balquhidder Research Group

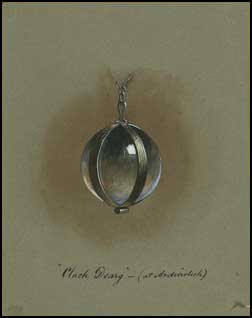

The Clach Dearg

The Stewarts of Ardvorlich owned a sweet red charm-stone known as the clach dearg (Gaelic for “red stone”, pronounced “klachk jeerk”), which, it is said, had the properties to cure sick cattle when they drank water in which it had been dipped. This stone was originally owned by the Stewarts of Balquhidder, and family tradition asserts that it was brought back from the Crusades. — I. Moncrieffe, The Highland Clans (London, 1967), 21.

Perthshire Diary 2 SEP 1745 has the following to say about the Clach Dearg:

Many of the old Highland chiefs were men of great sophistication and education. Yet they were also capable of accepting without question the efficacy and powers of certain ancient stones and talismans.

The Clach Dhearg (Red stone) of Ardvorlich is a case in point. It was said to have been brought back from the Crusades in the 14th Century. It was a crystal ball mounted in silver and was owned by the Stewarts of Balquhidder.

Owners of sick cattle from a large area would come with kegs of water to Ardvorlich. There, the custodian’s wife would dangle the stone by a chain in the water, rotating it three times clockwise while reciting a Gaelic charm. Providing the owner took the keg of water straight home without entering any house on the way the water was deemed a sure cure for sick cattle.

The importance of the Clach Dhearg was such that in a dispute over the chieftainship of the Stewarts of Balquhidder, the issue was settled on Mac Mhic Bhaltair because he had possession of the stone.

The Clach Dearg of Ardvorlich

Drawing by James Drummond (www.rls.org.uk)

Alexander Stewart, 1st of Ardvorlich

Alexander Stewart, 1st of Ardvorlich, b. Abt 1538, Port of Lochearn, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. 1622, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland. Alexander Stewart’s exact date and place of birth are uncertain. Alexander was the eldest son of James Mhor Stewart, in Port of Lochearn.

According to the Ardvorlich History, Alexander’s younger brother John was born in 1540 which would require Alexander to be born just prior to that. As his father was residing in Port of Lochearn (later renamed to St. Fillans), it is presumed that Alexander was born there.

Alexander Stewart acquired Ardvorlich (possibly “Ard-mhoirlich” in Gaelic meaning “the height of the great hollow”) in 1580 as a freeholder of the Crown. He became leader of a clan which, according to Duncan Stewart (1739), numbered about three hundred people. He also notes that Alexander was known by the Gaelic patronymic Mac-mhic-Bhaltair, “son of the son of Walter”. He was likely known as such, rather than “mac Sheamuis” (son of James), because the clan chiefship passed from his grandfather, Walter, to his uncle, James Stewart, 4th of Baldorran, then likely skipped over his own father to Alexander.

Duncan Stewart (1739) says:

“This Alexander, who purchased Ardvorlich, had the Irish epithet, Mac-mhic-Walter, that is, the son of Walter’s son, as had his brethren and posterity, to distinguish them from the Stewarts of Glenbucky and Garnafuaroe. The foresaid epithet likewise infers that Walter left but one son, viz James, who had issue. Alexander of Ardvorlich married Margaret Drummond, daughter to Drummond-Erinoch, by whom he had, 1 James, 2 William, 3 Duncan, and Isabel, married to John Stewart, great-grandfather to John Stewart of Glenbucky, likewise Janet, married to Duncan Stewart in Glenogle, ancestor to John Stewart of Hyndfield.”

According to The Castle Guy, the property of Ardvorlich was previously occupied by a family of MacKeans.

The main branch of the clan was also known as Sliochd Tigh nan Eileann (Descendants of the House of the Island) in reference to a fortified house on Loch Venachar which they held. This property was Portnellan which passed to Alexander’s younger brother, John, who was predecessor to the Stewarts of Annat.

Alexander’s brother-in-law, John Drummond of Drummonderinoch, who was keeper of the Royal Forest, found a group of MacGregors poaching in the forest. As punishment he cut off their ears and sent them home humiliated. The MacGregor clan rose in defense, killing Drummond and delivering his head to the dinner table of the Ardvorlich Stewarts while Alexander was away. At the sight of her brother’s severed head on her dinner table, Margaret allegedly went nuts and ran off into the woods not to be found for days. Further legend has it that she was pregnant at the time and the shock sent her into labour and she delivered James Beag in the forest.

In 1592 Alistair (Alexander) Stewart of Ardvorlich led a cattle raid in Lennox with two bagpipes leading the way. (see below)

Allied Marriages

Alexander sought to strengthen his ties to the rest of Clan Stewart of Balquhidder by marrying his daughters to the heads of the major branches. His daughter Janet married Duncan MacRobert Stewart, 2nd of Glenogle. His daughter Isabel married John Dubh Mor Stewart, 6th of Glenbuckie. His daughter Margaret married Andrew Stewart, 6th of Gartnafuaran.

In 1622, Alexander and “the haill remanent persounes of the name of Steuart duelland within Balquhidder and Stragartney” (“the whole remaining persons of the name of Stewart dwelling in Balquhidder and Strathgartney”) gave a Bond of assurance not to harm William, Earl of Menteith. (Gordon MacGregor, The Red Book of Scotland)

The Stewarts of Ardvorlich continue to hold this estate to this very day.

The Murder of John Drummond of Drummonderinoch

The Distress of Margaret Drummond of Drummonderinoch, wife of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Ardvorlich

And the Incredible Birth Story of James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich

[Warning – this story is rather gruesome]

Alexander Stewart of Ardvorlich was married to Margaret Drummond of Drummonderinoch. Her brother, John Drummond, 4th Laird of Drummonderinoch, was keeper of the royal forest near Balquhidder. One day John caught a group of MacGregors poaching in the forest. As punishment for poaching he cut off their ears and sent them home humiliated. (Some versions say that John Drummond hanged the poachers as this was their second offense, and that he clipped their ears on their first offense.)

The poachers ran home to their clansmen who were outraged at the humiliation brought upon their kin by John Drummond. The MacGregors vowed to have their revenge on Drummonderinoch and set out after him. When they found him, they killed him, cut off his head, wrapped his head in their tartan, and headed off to visit Drummond’s sister at the house of Ardvorlich.

When they arrived at Ardvorlich they found Alexander Stewart away and Margaret home alone. They asked for hospitality and were invited in. (In Highland culture, hospitality is an extremely important virtue. It would be a significant social sin to refuse hospitality to anyone at your door.) Margaret quickly brought bread, cheese, and drink, and then went off to the kitchen to prepare a more substantial meal for her guests. While Margaret was out of the room the MacGregors took the severed head of her brother and placed it on the dining table. They then proceeded to stuff her brother’s mouth with the bread and cheese she had brought them.

When Margaret returned to the dining room with the meal for her guests she was greeted by the gruesome severed head of her brother disgraced with her hospitable offerings. Margaret became hysterical (understandably) and ran from the house into the forest not to be heard from for days. To compound matters, Margaret was also pregnant at the time and nearly full-term.

When Alexander returned home, he was distraught and combed the woods for his pregnant wife, but to no avail. Servants claimed to see glimpses of Margaret on the fringes of the forest but then she would disappear into the trees again before anyone could catch her. Eventually she did return home, but with a surprise. According to family legend, while she’d been away in the forest she gave birth to her child at the side of a lochan subsequently called, Lochan an Mna (“The Lady’s Loch”) after the birth that took place there. (Peter McNaughton, Highland Strathearn) They named this son, James.

(Lochan na Mna is located at the top of the Ardvorlich Burn about 5 km above Ardvorlich House. It is not identified on OS maps, but is located right beside Creagan an Lochan.)

All lands and title were stripped from the MacGregors. The name MacGregor itself was outlawed. Anyone found using the name MacGregor could be killed without consequence. MacGregors either had to change their names or flee to the hills to avoid being killed. Anyone who was accused of a crime and who was able to capture or kill a MacGregor would receive a full pardon for their crime, regardless of how severe the crime was — even murderers were pardoned if they could bring a MacGregor to heel. This proscription lasted for over 100 years before it was finally lifted!

Additional photos by InJacobiteFootsteps

Lochan na Mna Lady’s Loch

Lochan na Mna (“The Lady’s Loch”) where Margaret Drummond of Drummonderinoch, wife of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Ardvorlich, gave birth all alone to James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich. Photo by InJacobiteFootsteps

Lochan na Mna with Ben Vorlich in the background

Lochan na Mna with snow-capped Ben Vorlich in the background. This is where James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich, was born. Photo by InJacobiteFootsteps.

A Brazen Cattle Raid on Lennox (1592)

Lest one be mistaken so as to think that the Ardvorlich Stewarts were only the victims of crime and violence, in 1592 Alistair (Alexander) Stewart of Ardvorlich led a cattle raid on Drumquhassil near Drymen in Lennox. Now cattle raiding into the Lowlands was certainly not uncommon among Highland clans. Highlanders were known to slip down in the dead of night into the Lowland farms, sneak away with a few head, and disappear into the darkness of the night time Highland hills. However Alistair Stewart of Ardvorlich apparently felt no need for the cover of darkness nor anything quite so clandestine. He felt so confident that he marched down into the Lennox in the middle of the day with his clan behind him and two bagpipers leading the way announcing their impending arrival.

According to James Stewart in The Settlements of Western Perthshire, “…from the writ against the Stewarts of Ardvorlich for their raiding of the Lennox in 1592. The spoil consisted of three hundred sheep, one hundred and ninety-six cattle, and sixty-six horses.” (p.73)

Another interesting fact about this raid is that the Stewarts of Ardvorlich’s former residence of Baldorran was also located in Lennox about ten miles from Drumquhassil. So they were really poaching their own former neighbours!

Marriage and Children

Alexander Stewart married to Margaret Drummond, of Drummonderinoch, b. Abt 1560, Drummonderinoch, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, daughter of John Drummond, 3rd of Drummonderinoch. Alexander and Margaret had the following children:

1. Janet Stewart, of Ardvorlich, b. Abt 1580, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Janet Stewart, of Ardvorlich, b. Abt 1580, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN.

Janet is shown in Duncan Stewart’s 1739 History of the Stewarts as having married Duncan Stewart of Glenogle. There was only one Duncan of Glenogle who would be contemporary with Janet. Thus we show that Janet Stewart married Duncan McRobert Stewart, 3rd in Glenogle.

Janet Stewart married Duncan McRobert Stewart, 3rd in Glenogle, b. Abt 1538, Baldorran, Campsie, Stirling, Scotland, d. 1622, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland. They had the following children who will be presented in full on our Stewarts of Glenogle page (when that page is migrated over from our old website).

- Robert Stewart, 4th of Glenogle, b. Abt 1600, Glenogle, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

- Duncan Stewart, in Monachyle, b. Abt 1605, Glenogle, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

- Alexander Stewart, in Achtow, b. Abt 1610, Glenogle, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

2. Isabel Stewart, of Ardvorlich, b. Abt 1585, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Isabel Stewart, of Ardvorlich, b. Abt 1585, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN.

According to Duncan Stewart (1739), Isabel married John Stewart, “great-grandfather of John Stewart of Glebuckie.”

Isabel married John Dubh Mor Stewart, 6th of Glenbuckie, b. Abt 1575, Glenbuckie, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN. They had the following children who will be presented in full on our Stewarts of Glenbuckie page when it is migrated over from our old website.

- Duncan Stewart, b. Abt 1608, Glenbuckie, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN. - Alexander Stewart, 7th of Glenbuckie, b. Abt 1610, Glenbuckie, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 1676

, d. 1676 - James Stewart, b. Abt 1612, Glenbuckie, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 1673, Glenfinglas, Callander, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 1673, Glenfinglas, Callander, Perthshire, Scotland - Isabel Stewart, b. Abt 1620, Glenbuckie, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. UNKNOWN

, d. UNKNOWN - Several Daughters Stewart, b. Aft 1620, Glenbuckie, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland

3. Major James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich, b. Abt Oct 1589, Lady's Loch on Ben Vorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. 1658, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland

Major James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich, b. Abt Oct 1589, Lady’s Loch on Ben Vorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. 1658, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland. His story is presented below.

4. William MacAlasdair Stewart, 1st of Balimeanoch, b. Abt 1595, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. Bef 1 Dec 1648, Scotland

William MacAlasdair Stewart, 1st of Balimeanach, b. Abt 1595, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland ![]() , d. Bef 1 Dec 1648, Scotland.

, d. Bef 1 Dec 1648, Scotland.

William was the progenitor of the Stewarts of Ardvorlich Branch II (the Stewarts of Balimeanoch), next door to Ardvorlich. When the original branch of Ardvorlich died out in the 18th century, the estate and title of Ardvorlich were inherited by the Balimeanoch branch.

William’s information will be presented on our Stewarts in Balimeanach page.

5. Duncan Oag Stewart, of Auchraig and Inchcallbeg, b. Abt 1597, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. Apr 1632

Duncan Oag Stewart, of Auchraig and Inchcallbeg, b. Abt 1597, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. Apr 1632.

Duncan Oag Stewart was the progenitor of Branch III: Stewarts in Auchrig and Branch IV: Stewarts in Letter. His descendants can be found on those pages.

6. Margaret Stewart, of Ardvorlich, b. Abt 1600, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Margaret Stewart, of Ardvorlich, b. Abt 11600, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN. Maragaret married Andrew Stewart, 6th of Gartnafuaran, b. Abt 1603, Gartnafuaran, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN. They had the following children. Their story is presented on our Stewarts of Gartnafuaran page (not yet published).

- Alexander Stewart, b. Abt 1623, Gartnafuaran, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland, d. Bef 1708

- Walter Stewart, 7th of Gartnafuaran, b. 1625, Gartnafuaran, Balquhidder, Perthshire, Scotland, d. Aft 1654

7. Daughter Stewart, b. Abt 1605, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Daughter Stewart, b. Abt 1605, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN. Alexander and Margaret had a daughter whose name is not recorded. She married Allan Stewart, 6th of Appin, b. Abt 1580, Appin, Argyll, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN.

Major James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich

Major James Beag Stewart, 2nd of Ardvorlich, b. Abt Oct 1589, Lady’s Loch on Ben Vorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland ![]() , d. 1658, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 1658, Ardvorlich, Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland ![]() . He was the eldest son of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Ardvorlich, shown above.

. He was the eldest son of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Ardvorlich, shown above.

The son of Alexander Stewart and Margaret Drummond, who was allegedly born by the side of a small loch in the mountains in 1589, was named James Beag Stewart. (“Beag” is a Gaelic nickname which means “small.”) Contrary to his nickname of “little”, this James Beag Stewart apparently grew to be a large, powerful, and angry man. It is said that he could cause a man’s fingernails to bleed just by shaking his hand.

Lifelong Vendetta Against the MacGregors

James spent his entire life exacting revenge on the MacGregors for the murder of his uncle John Drummond of Drummonderinoch, taking full advantage of the liberties accorded by the proscription of Clan Gregor. On one occasion James took a dozen MacGregors and hanged them himself near Comrie rather than turn them over to the Crown for prosecution. (Some sources credit this execution to James’ father, Alexander Stewart.)

Sir Walter Scott – A Legend of Montrose

James Beag Stewart led a life worth writing about, and the story of his life is featured in the book, A Legend of Montrose, by Sir Walter Scott. Scott’s character, Alan Macauley (shown below), is based on the life of James Beag Stewart.

James’ Dream Saves Ardvorlich

When dozing, he had a dream that told him that something was wrong and happening at Ardvorlich. Awakened, he rushed there and found a party of MacDonalds driving his cattle from the barns, and about to set fire to his house. A poor wee lassie was trying to fight off the raiders with little success. Stewart drew his weapon; a gun called “Gunna Breachd” and fired killing the man attacking the maid. Then, accompanied by other Stewarts, he counter-attacked the MacDonalds and drove them off. They left behind seven dead who were dragged to the lochside and buried near the mouth of the Ardvorlich Burn. These were discovered later by some workmen who were digging the foundations of a boathouse and who came across their skeletons. Later a stone was placed there which states “Near this spot were interred the bodies of 7 McDonalds killed when attempting to harry Ardvorlich Anno Domini 1620.” — Peter McNaughton (Highland Strathearn)

Another source claims that the seven MacDonalds were guided by a MacGregor. (From the former www.scottish-towns.co.uk website.)

The Legend of the Clearing of Glen Finglas

Sometime around the turn of the 17th century, a group of MacGregors allegedly forcibly occupied Glen Finglas in Callander parish, just south of Glen Buckie. They were said to have been the cause of great mischief there. These lands belonged at that time to the Earl of Moray and he allegedly wanted the MacGregors removed. The Earl’s deputy forester was Duncan Stewart, 5th of Glenbuckie, who had a natural son, John Dubh Beag Stewart. The Earl is said to have commission John Dubh Beag Stewart and James Beag Stewart of Ardvorlich (as clan chief) to raise a force of men and forcibly remove the MacGregor’s from Glen Finglas. James readily agreed to this task as yet another opportunity to exact his revenge on the MacGregors.

The legend continues that sometime around the year 1620, the Stewarts successfully evicted the MacGregors from Glen Finglas and captured the chief of the MacGregors. For their efforts, James Beag Stewart was granted the lands of Glen Finglas. He divided these lands among the major cadet branches of the Stewarts of Balquhidder and gave one-quarter to the family of the Stewarts of Glenbuckie, one-quarter to the family of the Stewarts of Gartnafuaran, one-eighth to the Stewarts of Annat and kept the remaining three-eights for himself.

The only problem with this legend is that it isn’t true. There is no record of any trouble-making MacGregors in Glen Finglas or of any eviction sanctioned by the Earl of Moray. (The legend is explained in detail on our Stewarts of Glen Finglas page.)

James is cited in the following two bonds:

-

- 1622 Bond by Alexander Stewart in Ardworlich [Ardvorlich], James Stewart, his eldest son, Alexander Stewart in Portnellane [Portnellan]; Andrew Stewart of Blairgarrie, Duncan Stewart in Monochole [Monachyle], Alexander Stewart in Glenogle [Glen Ogle]; John Dow Stewart [of Glenbuckie] in Glenfinglas [Glen Finglas], Walter Stewart, his brother german, and Duncan Stewart in [illegible]; for themselves and “the haill remanent persounes of the name of Steuart duelland [dwelling] within Balquhidder and Stragartnay [Strath Gartney]”, whereby they bind themselves to William [Graham], earl of Monteth [Menteith], Lord Kilpont and Elistoun [Lennieston], promising that if they at any time injure or wrong said earl, they will pay to him 100 merks Scots; that they will not aid anyone put to the horn at his instance, under penalty of 500 merks Scots in case of failure; and that they will not conceal any danger which may befall said earl by day or night, but will inform him of same with all possible diligence.” (Gordon MacGregor, The Red Book of Scotland)

- 11 JUN 1622. Bond by James Stewart, son of Alexander Stewart in Ardvurliche [Ardvorlich], and Alexander McKen (MacIain) Stewart in Portnellen, to William, Earl of Montethe [Menteith], who has become cautioner to produce Andrew Stewart, son of Alexander Stewart in Glenogle, before the lords of secret council, whereby they undertake to produce said Alexander accordingly, under penalty of 500 merks. (Gordon MacGregor, The Red Book of Scotland)

James Beag was infeft in the lands of Ardvorlich by Sasine of 18 July 1627, in which he is styled legitimate son of Allister Stewart in Ardvorlich. (Gordon MacGregor, The Red Book of Scotland)

James Beag was granted letters of Reversion for the lands of Port of Lochearn (present-day St. Fillans) and Moral (in Glen Tarken on Loch Earn) to John Drummond, Earl of Perth, in 1627. (Gordon MacGregor, The Red Book of Scotland)

The Murder of John Graham, Lord Kilpont

In the Scottish civil wars of the 17th century, James Beag Stewart initially sided with James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose, and the Royalist cause in support of King Charles I and in opposition to the Covenanter dominated Scottish Parlianment side. James Beag attained the rank of Major in Montrose’s army and fought in the opening battle of the campaign at Tibbermuir.

Battle of Tippermuir: 1st September 1644

James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, with 2000 Highlanders and Irish defeated a Covenanter force of 6000 under Lord Elcho at Tippermuir (Tibbermore in Gaelic) and occupied Perth. This was the first battle in Montrose’s failed rebellion in support of King Charles I carried out while the main Scottish army was in England supporting the Government forces there. Few died in the battle, but an estimated 2000 died in the subsequent massacre – this puts Tippermore at about the same level of post-battle massacre as Culloden!

Montrose’s most loyal aid was John Graham, Lord Kilpont, eldest son of William Graham, Earl of Menteith and Airth. Kilpont was described as a “very close friend” of James Beag Stewart. Today we can safely say that the evidence shows they were lovers. In fact, the Graham account of the murder (shown below) specifically states “After the banquet a quarrel of some sort arose between Kilpont and his intimate friend, James Stewart of Ardvoirlich, who had shared his tent and his bed….” But in the 17th century such an accusation was solidly denied by the house of Ardvorlich. The Stewart family claimed that they were just “very intimate friends who often shared a tent”.

At one point James Beag and Lord Kilpont had a dispute (allegedly fuelled by a great deal of whisky) that became physical. During the altercation Kilpont was fatally stabbed by James Beag. James not only killed his “very close friend”, but he simultaneously killed the most loyal aid of his patron, Montrose. James had to flee the wrath of Montrose. And he did so with such haste that he even abandoned his own son, Harry, who had been mortally wounded on the battlefield, and left him to die of his injuries. James fled to the side of Montrose’s enemy, Campbell, the Duke of Argyll.

Kilpont’s wife, who was also a Graham, was so angered by the incident that she swore a blood feud against the Stewarts of Ardvorlich.

The Pardoning of James Beag Stewart & Kin

Because Argyll was loyal to the Crown and was the eventual victor in the war, James Beag Stewart, as a follower of Argyll, was branded a hero instead of a murderer and was granted a full pardon for the murder he committed. The murder was considered “justifiable” by the Crown as the victim was a “rebel”.

The full transcript of the Parliamentary Record of the Pardon for James Stewart on 1 March 1645 is enclosed. It reveals some interesting facts. Most notably that it is not just James Beag Stewart who is named in the pardon. Also pardoned are several close kinsmen of the Stewarts of Balquhidder, including his son, his brothers-in-law, and his nephew. Those pardoned included: Robert Stewart, son of James of Ardvorlich, Duncan McRobert Stewart in Balquhidder (2nd of Glen Ogle, and brother-in-law of James Beag Stewart of Ardvorlich), Andrew Stewart in Balquhidder (6th of Gartnafuaran and brother-in-law of James Beag Stewart of Ardvorlich), and Walter Stewart in Glenfinglas (son of Andrew Stewart, 6th of Gartnafuaran, and nephew of James Beag Stewart of Ardvorlich). All of these men were close kin of James. It says they all initially served Montrose and then, having realized the error of their ways, they sought to persuade Kilpont to join them in going over to Campbell’s side. Kilpont objected. The fight broke out between Kilpont and Ardvorlich, and Ardvorlich had to kill Kilpont in self-defence. All of them are accounted as former rebels whose later repentance and defection to the “right side” warranted their pardon.

The inclusion of the other clansmen raises some interesting possible interpretations. It could imply that the murder of Kilpont may not have been solely motivated by drunken rage, but may indeed have had political overtones. Or it could mean that the other Stewart clansmen, having discovered that their chief had just murdered Kilpont, either feared for their own lives too or they didn’t want to abandon their chief and defected with him.

The popular version of the murder of Lord Kilpont attributes James’ motives to nothing more than an uncontrollable rage. He was reputed to be a man with a wicked temper who would kill without a second thought (which seems to be an accurate description), so he was accused of killing Kilpont in cold blood without provocation, and was branded a murderer. That’s the version that was committed to history by Bishop Wishart, Chaplain to Montrose, and to fiction by Sir Walter Scott. However in a preface to Scott’s book written in the early 19th century, the publisher tells a different version of the story as told to him by Robert Stewart, the 7th Laird of Ardvorlich.

Robert of Ardvorlich denies the angry temperament of James Beag; he denies the homosexual relationship between James Beag and Kilpont and he denies that the murder was in cold blood; he claims that the killing was justifiable. He alleges that the dispute arose because of atrocities committed on the lands of Ardvorlich by Irish conscripts who were fighting for Montrose. This is a reasonable suggestion as those same Irish conscripts, under Colkitto, Montrose’s lieutenant general, burned Ardveich on the north shore of Loch Earn. James Beag confronted Kilpont about the matter seeking damages from Montrose. There was a disagreement over the matter and a brawl ensued in which Kilpont was accidentally stabbed. Robert of Ardvorlich also alleges that Kilpont was involved in some ill-business behind the back of Montrose which James Beag discovered and which fuelled Kilpont’s anger.

What is significant for researchers of the later cadet branch, the Stewarts of Dalveich (this author’s own family), is not so much the second version of the events, but how this second version of the story came to be known. According to the publisher’s preface in A Legend of Montrose, Robert Stewart, 7th Laird of Ardvorlich, learned of the “true” version of the events from a distant cousin who was descended from James Beag’s natural son John Dubh Mhor Stewart (see below). John Dubh Mohr claimed to have been a first-hand witness to the dispute between his father and Lord Kilpont and passed on the “true” version through his descendants.

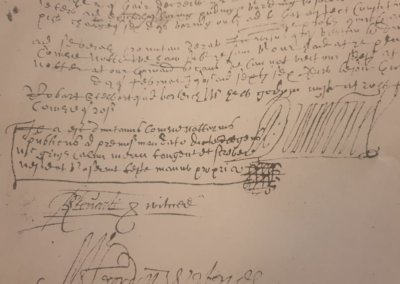

- The Pardoning of James Stewart

- A Legend of Montrose: Introduction, by Sir Walter Scott

- The Stewarts of Ardvorlich's Version of the Murder of Lord Kilpont

- The Graham Version of the Murder of Kilpont (Part 1)

- The Graham Version of the Murder of Kilpont (Part 2)

- The Graham Version of the Murder of Kilpont (Part 3)

- The Murder of Lord Kilpont, by Jenn Chamberlain, Stewart Society Archivist

From the original Parliamentary record, 1 March 1645

Ratification of James Stewart’s pardon for the killing of the Lord Kilpont

“Forasmuch as the late John, lord Kilpont (being employed in public service in the month of August last against James Graham, then earl of Montrose, the Irish rebels and their associates) did not only treasonably join himself but also treacherously trained a great number of his majesty’s subjects (about 400 persons or thereby, who came with him for defence of the country) to join also with the said rebels, of the which number were James Stewart of Ardvorlich, Robert Stewart, his son, Duncan MacRobert Stewart in Balquhidder, Andrew Stewart there, Walter Stewart in Glen Finglas and John Growder in Glassinseid, friends to the said James, who shortly thereafter, repenting of his error in joining with the said rebels and abhorring their cruelty, resolved with his said friends to forsake their wicked company and intimated this resolution to the said late Lord Kilpont. But he out of his malignant disposition opposed the same and fell in a struggle with the said James, who, for his own relief, was forced to kill him at the kirk of Collace with two Irish rebels who resisted his escape. And so he left happily with his said son and friends and came straight to the marquis of Argyll and offered their service to the country. Whose carriage in this particular being considered by the committee of estates, they by their act of 10 December last found and declared that the said James Stewart did good service to this kingdom in killing the said Lord Kilpont and two Irish rebels aforesaid being in actual rebellion against the country and approved of what he did therein; and in regard thereof and of the said James, his son and friends retiring from the said rebels and joining with the country did fully and freely pardon them for their said joining with the rebels and their associates or for being in any way accessory, actors, art and part of and to any of the crimes, misdeeds or malversations done by themselves or by the rebels and their associates or any of them during the time they were with the said rebels, and declared them free in their persons, estates and goods of any thing that can be laid to their charge thereof or for killing the said Lord Kilpont and two Irish rebels aforesaid in time coming, and did by the said act discharge all judges, officers and magistrates (both to burgh and landward) and others of his majesty’s subjects whatsoever to trouble or molest the said James, his son or friends above-mentioned for the cause aforesaid in judgement or outwith or to direct letters against them for the same or use any judicial process against them for that effect or to offer wrong or injury to them or any of them in their persons or goods in time coming for the premises, certifying that those that should do in the contrary should be esteemed as having committed a wrong against this kingdom; and the committee recommended the ratification of the said act to this present session of parliament, as the act more fully purports. And now the estates of parliament, presently convened in the second session of this first triennial parliament by virtue of the last act of the last parliament held by his majesty and three estates in 1641, taking the same and particulars contained therein into their special consideration and acknowledging the equity thereof, they do therefore ratify and approve the same act, all articles and clauses thereof and interpose their authority thereto in all points to have the strength of an act of parliament in favour of the said James Stewart of Ardvorlich, his said son and friends above-written in time coming.”

The act of Committee proceeds to prohibit all judicatories and judges whomsoever, from any attempt to bring the parties to justice, or entertain the case against them in any shape, and the parliament taking all this into their special consideration, “and acknowledging the equity thereof,” confirms and ratifies the same in favour of James Stewart, his son, and his other friends named.

A Legend of Montrose was written chiefly with a view to place before the reader the melancholy fate of John Lord Kilpont, eldest son of William Earl of Airth and Menteith, and the singular circumstances attending the birth and history of James Stewart of Ardvoirlich, by whose hand the unfortunate nobleman fell.

Our subject leads us to talk of deadly feuds, and we must begin with one still more ancient than that to which our story relates. During the reign of James IV., a great feud between the powerful families of Drummond and Murray divided Perthshire. The former, being the most numerous and powerful, cooped up eight score of the Murrays in the kirk of Monivaird, and set fire to it. The wives and the children of the ill-fated men, who had also found shelter in the church, perished by the same conflagration. One man, named David Murray, escaped by the humanity of one of the Drummonds, who received him in his arms as he leaped from amongst the flames. As King James IV. ruled with more activity than most of his predecessors, this cruel deed was severely revenged, and several of the perpetrators were beheaded at Stirling. In consequence of the prosecution against his clan, the Drummond by whose assistance David Murray had escaped, fled to Ireland, until, by means of the person whose life he had saved, he was permitted to return to Scotland, where he and his descendants were distinguished by the name of Drummond-Eirinich, or Ernoch, that is, Drummond of Ireland; and the same title was bestowed on their estate.

The Drummond-ernoch of James the Sixth’s time was a king’s forester in the forest of Glenartney, and chanced to be employed there in search of venison about the year 1588, or early in 1589. This forest was adjacent to the chief haunts of the MacGregors, or a particular race of them, known by the title of MacEagh, or Children of the Mist. They considered the forester’s hunting in their vicinity as an aggression, or perhaps they had him at feud, for the apprehension or slaughter of some of their own name, or for some similar reason. This tribe of MacGregors were outlawed and persecuted, as the reader may see in the Introduction to ROB ROY; and every man’s hand being against them, their hand was of course directed against every man. In short, they surprised and slew Drummond-ernoch, cut off his head, and carried it with them, wrapt in the corner of one of their plaids.

In the full exultation of vengeance, they stopped at the house of Ardvoirlich and demanded refreshment, which the lady, a sister of the murdered Drummond-ernoch (her husband being absent), was afraid or unwilling to refuse. She caused bread and cheese to be placed before them, and gave directions for more substantial refreshments to be prepared. While she was absent with this hospitable intention, the barbarians placed the head of her brother on the table, filling the mouth with bread and cheese, and bidding him eat, for many a merry meal he had eaten in that house.

The poor woman returning, and beholding this dreadful sight, shrieked aloud, and fled into the woods, where, as described in the romance, she roamed a raving maniac, and for some time secreted herself from all living society. Some remaining instinctive feeling brought her at length to steal a glance from a distance at the maidens while they milked the cows, which being observed, her husband, Ardvoirlich, had her conveyed back to her home, and detained her there till she gave birth to a child, of whom she had been pregnant; after which she was observed gradually to recover her mental faculties.

Meanwhile the outlaws had carried to the utmost their insults against the regal authority, which indeed, as exercised, they had little reason for respecting. They bore the same bloody trophy, which they had so savagely exhibited to the lady of Ardvoirlich, into the old church of Balquidder, nearly in the centre of their country, where the Laird of MacGregor and all his clan being convened for the purpose, laid their hands successively on the dead man’s head, and swore, in heathenish and barbarous manner, to defend the author of the deed. This fierce and vindictive combination gave the author’s late and lamented friend, Sir Alexander Boswell, Bart., subject for a spirited poem, entitled “Clan-Alpin’s Vow,” which was printed, but not, I believe, published, in 1811 [See Appendix No. I].

The fact is ascertained by a proclamation from the Privy Council, dated 4th February, 1589, directing letters of fire and sword against the MacGregors [See Appendix No. II]. This fearful commission was executed with uncommon fury. The late excellent John Buchanan of Cambusmore showed the author some correspondence between his ancestor, the Laird of Buchanan, and Lord Drummond, about sweeping certain valleys with their followers, on a fixed time and rendezvous, and “taking sweet revenge for the death of their cousin, Drummond-ernoch.” In spite of all, however, that could be done, the devoted tribe of MacGregor still bred up survivors to sustain and to inflict new cruelties and injuries.

[I embrace the opportunity given me by a second mention of this tribe, to notice an error, which imputes to an individual named Ciar Mohr MacGregor, the slaughter of the students at the battle of Glenfruin. I am informed from the authority of John Gregorson, Esq., that the chieftain so named was dead nearly a century before the battle in question, and could not, therefore, have done the cruel action mentioned. The mistake does not rest with me, as I disclaimed being responsible for the tradition while I quoted it, but with vulgar fame, which is always disposed to ascribe remarkable actions to a remarkable name.-See the erroneous passage, ROB ROY, Introduction; and so soft sleep the offended phantom of Dugald Ciar Mohr.

It is with mingled pleasure and shame that I record the more important error, of having announced as deceased my learned acquaintance, the Rev. Dr. Grahame, minister of Aberfoil.-See ROB ROY, p.360. I cannot now recollect the precise ground of my depriving my learned and excellent friend of his existence, unless, like Mr. Kirke, his predecessor in the parish, the excellent Doctor had made a short trip to Fairyland, with whose wonders he is so well acquainted. But however I may have been misled, my regret is most sincere for having spread such a rumour; and no one can be more gratified than I that the report, however I have been induced to credit and give it currency, is a false one, and that Dr. Grahame is still the living pastor of Aberfoil, for the delight and instruction of his brother antiquaries.]

Meanwhile Young James Stewart of Ardvoirlich grew up to manhood uncommonly tall, strong, and active, with such power in the grasp of his hand in particular, as could force the blood from beneath the nails of the persons who contended with him in this feat of strength. His temper was moody, fierce, and irascible; yet he must have had some ostensible good qualities, as he was greatly beloved by Lord Kilpont, the eldest son of the Earl of Airth and Menteith.

This gallant young nobleman joined Montrose in the setting up his standard in 1644, just before the decisive battle at Tippermuir, on the 1st September in that year. At that time, Stewart of Ardvoirlich shared the confidence of the young Lord by day, and his bed by night, when, about four or five days after the battle, Ardvoirlich, either from a fit of sudden fury or deep malice long entertained against his unsuspecting friend, stabbed Lord Kilpont to the heart, and escaped from the camp of Montrose, having killed a sentinel who attempted to detain him. Bishop Guthrie gives us a reason for this villainous action, that Lord Kilpont had rejected with abhorrence a proposal of Ardvoirlich to assassinate Montrose. But it does not appear that there is any authority for this charge, which rests on mere suspicion. Ardvoirlich, the assassin, certainly did fly to the Covenanters, and was employed and promoted by them. He obtained a pardon for the slaughter of Lord Kilpont, confirmed by Parliament in 1634, and was made Major of Argyle’s regiment in 1648. Such are the facts of the tale here given as a Legend of Montrose’s wars. The reader will find they are considerably altered in the fictitious narrative.

POSTSCRIPT (to the INTRODUCTION TO A LEGEND OF MONTROSE, by Sir Walter Scott)

While these pages were passing through the press, the author received a letter from the present Robert Stewart of Ardvoirlich, favouring him with the account of the unhappy slaughter of Lord Kilpont, differing from, and more probable than, that given by Bishop Wishart, whose narrative infers either insanity or the blackest treachery on the part of James Stewart of Ardvoirlich, the ancestor of the present family of that name. It is but fair to give the entire communication as received from my respected correspondent, which is more minute than the histories of the period.

“Although I have not the honour of being personally known to you, I hope you will excuse the liberty I now take, in addressing you on the subject of a transaction more than once alluded to by you, in which an ancestor of mine was unhappily concerned. I allude to the slaughter of Lord Kilpont, son of the Earl of Airth and Monteith, in 1644, by James Stewart of Ardvoirlich. As the cause of this unhappy event, and the quarrel which led to it, have never been correctly stated in any history of the period in which it took place, I am induced, in consequence of your having, in the second series of your admirable Tales on the History of Scotland, adopted Wishart’s version of the transaction, and being aware that your having done so will stamp it with an authenticity which it does not merit, and with a view, as far as possible, to do justice to the memory of my unfortunate ancestor, to send you the account of this affair as it has been handed down in the family.

“James Stewart of Ardvoirlich, who lived in the early part of the 17th century, and who was the unlucky cause of the slaughter of Lord Kilpont, as before mentioned, was appointed to the command of one of several independent companies raised in the Highlands at the commencement of the troubles in the reign of Charles I.; another of these companies was under the command of Lord Kilpont, and a strong intimacy, strengthened by a distant relationship, subsisted between them. When Montrose raised the royal standard, Ardvoirlich was one of the first to declare for him, and is said to have been a principal means of bringing over Lord Kilpont to the same cause; and they accordingly, along with Sir John Drummond and their respective followers, joined Montrose, as recorded by Wishart, at Buchanty. While they served together, so strong was their intimacy, that they lived and slept in the same tent.

“In the meantime, Montrose had been joined by the Irish under the command of Alexander Macdonald; these, on their march to join Montrose, had committed some excesses on lands belonging to Ardvoirlich, which lay in the line of their march from the west coast. Of this Ardvoirlich complained to Montrose, who, probably wishing as much as possible to conciliate his new allies, treated it in rather an evasive manner. Ardvoirlich, who was a man of violent passions, having failed to receive such satisfaction as he required, challenged Macdonald to single combat. Before they met, however, Montrose, on the information and by advice, as it is said, of Kilpont, laid them both under arrest. Montrose, seeing the evils of such a feud at such a critical time, effected a sort of reconciliation between them, and forced them to shake hands in his presence; when, it was said, that Ardvoirlich, who was a very powerful man, took such a hold of Macdonald’s hand as to make the blood start from his fingers. Still, it would appear, Ardvoirlich was by no means reconciled.

“A few days after the battle of Tippermuir, when Montrose with his army was encamped at Collace, an entertainment was given by him to his officers, in honour of the victory he had obtained, and Kilpont and his comrade Ardvoirlich were of the party. After returning to their quarters, Ardvoirlich, who seemed still to brood over his quarrel with Macdonald, and being heated with drink, began to blame Lord Kilpont for the part he had taken in preventing his obtaining redress, and reflecting against Montrose for not allowing him what he considered proper reparation. Kilpont of course defended the conduct of himself and his relative Montrose, till their argument came to high words; and finally, from the state they were both in, by an easy transition, to blows, when Ardvoirlich, with his dirk, struck Kilpont dead on the spot. He immediately fled, and under the cover of a thick mist escaped pursuit, leaving his eldest son Henry, who had been mortally wounded at Tippermuir, on his deathbed.

“His followers immediately withdrew from Montrose, and no course remained for him but to throw himself into the arms of the opposite faction, by whom he was well received. His name is frequently mentioned in Leslie’s campaigns, and on more than one occasion he is mentioned as having afforded protection to several of his former friends through his interest with Leslie, when the King’s cause became desperate.

“The foregoing account of this unfortunate transaction, I am well aware, differs materially from the account given by Wishart, who alleges that Stewart had laid a plot for the assassination of Montrose, and that he murdered Lord Kilpont in consequence of his refusal to participate in his design. Now, I may be allowed to remark, that besides Wishart having always been regarded as a partial historian, and very questionable authority on any subject connected with the motives or conduct of those who differed from him in opinion, that even had Stewart formed such a design, Kilpont, from his name and connexions, was likely to be the very last man of whom Stewart would choose to make a confidant and accomplice. On the other hand, the above account, though never, that I am aware, before hinted at, has been a constant tradition in the family; and, from the comparative recent date of the transaction, and the sources from which the tradition has been derived, I have no reason to doubt its perfect authenticity. It was most circumstantially detailed as above, given to my father, Mr. Stewart, now of Ardvoirlich, many years ago, by a man nearly connected with the family, who lived to the age of 100. This man was a great-grandson of James Stewart, by a natural son John, of whom many stories are still current in this country, under his appellation of JOHN DHU MHOR. This John was with his father at the time, and of course was a witness of the whole transaction; he lived till a considerable time after the Revolution, and it was from him that my father’s informant, who was a man before his grandfather, John dhu Mhor’s death, received the information as above stated.

“I have many apologies to offer for trespassing so long on your patience; but I felt a natural desire, if possible, to correct what I conceive to be a groundless imputation on the memory of my ancestor, before it shall come to be considered as a matter of History. That he was a man of violent passions and singular temper, I do not pretend to deny, as many traditions still current in this country amply verify; but that he was capable of forming a design to assassinate Montrose, the whole tenor of his former conduct and principles contradict. That he was obliged to join the opposite party, was merely a matter of safety, while Kilpont had so many powerful friends and connexions able and ready to avenge his death.

“I have only to add, that you have my full permission to make what use of this communication you please, and either to reject it altogether, or allow it such credit as you think it deserves; and I shall be ready at all times to furnish you with any further information on this subject which you may require, and which it may be in my power to afford.

“ARDVOIRLICH, 15TH JANUARY, 1830.”

The publication of a statement so particular, and probably so correct, is a debt due to the memory of James Stewart; the victim, it would seem, of his own violent passions, but perhaps incapable of an act of premeditated treachery.

ABBOTSFORD, 1ST AUGUST, 1830.

From The Lake of Menteith – Its Islands and Vicinity, With Historical Accounts of the Priory of Inchmahome and the Earldom of Menteith – By A. F. Hutchinson, 1899

APPENDIX – The Murder of Lord Kilpont at Collace

John, Lord Kilpont, was born in or about 1633. ‘When his father held the title of Earl of Strathern, [sic. He never held the title of Earl of Strathearn. He sought the title and failed and was granted the title of Earl of Airth after insulting the king.] he married Lady Mary Keith, eldest daughter of the Earl Marischal, receiving with her a dowry of £30,000 Scots, while the lady was infeft in the baronies of Kilbride and Kilpont, and received an annuity of 1000 merks out of the barony of Drummond. The contract is dated 11th April, 1632, and the marriage took place in the coarse of that year. Lord Kilpont acted as his father’s assistant in the justioiarship of Menteith, and in that capacity was instrumental in bringing to justice the noted robber, John Dhu Macgregor. For this service he was thanked by the King in 1636. He also received a letter of thanks in 1639 for his steady adherence to the King’s interest as against the Covenanters.

In 1644 the Committee of Estates authorised him to assemble the men of Menteith, Lennox, and Keir, in order to guard the passages to Perth against the Irish levies who were on their march from the west. With this force, amounting to about 400 men, he was posted at the hill of Buchanty, in Glenalmond, when he was met by Montrose at the head of the Irish and Highland troops, and so far from resisting, he went over to him with the whole body of troops under his command.

The battle of Tibbermuir was fought on the 1st of September. After a rest of a few days in Perth, Montrose crossed the Tay on the 5th of September, and pitched his camp at Collace. That night he gave an entertainment to his officers to celebrate the victory at Tibbermuir. After the banquet a quarrel of some sort arose between Kilpont and his intimate friend, James Stewart of Ardvoirlioh, who had shared hie tent and his bed, which ended in Stewart stabbing his friend with hie dagger and escaping from the camp. The murderer fled to the Covenanting army, where he was received by Argyll, and promoted ultimately to the rank of Major. The body of Lord Kilpont was conveyed to Menteith. and interred in the Chapter House of the Priory of Inchmahome.1 Lady Kilpont was so affected by the death of her husband that she lost her reason. A bitter feud which lasted long between the Grahams of Menteith and their friends and the Stewarts of Lochearnside was another consequence. Kilpont’s son was a boy of about ten years of age at the time of his father’s death, but he never forgot the circumstances. At the very earliest opportunity be had, that is, immediately after the Restoration in 1660, he tried to open the question of his father’s murder by a petition to the King. After his accession to the earldom, he addressed the King again on the subject. Neither of these petitions had any effect. But the Earl continued to cherish his feeling of resentment, and as late as 1681, in a letter to the Marquis of Montrose, he refers to one Robert Stewart, who had purchased Stragartney, as “the treterous son of that cruell murderer of my faither, who was his Lord and Master.”2

The motive of Ardvoirlich in this slaughter of his friend is obscure, and the accounts are somewhat conflicting. The sources of information in regard to it are three. First, there is the story as told by Wishart, the Chaplain of Montrose. This was the version that was before Sir Walter Scott when he wrote the Legend of Montrose, and it of course reports the incident from the Royalist point of view. Next there is the account handed down in the Ardvoirlich family, and sent by one of the members of that family to Sir Walter, who published it in a postscript to his story.

1 See chap iv. p. 111

2 Letter in the Red Book of Menteith, ii., p. 192.

That, as might be expected, puts the action of Stewart in a distinctly more favourable light. And, in the third place, there is the statement of the circumstances in the Act of Parliament which ratified the pardon for the deed previously granted by the Privy Council, which-if it may not be held as an absolutely impartial statement-may at least be taken as putting the case in a light that was not regarded as unfavourable to Ardvoirlich.

Wishart accuses Ardvoirlioh, whom he calls “a base slave,” of a plot to murder Montrose. He endeavoured to draw Kilpont into the plot, and when the latter expressed his detestation of the villainy, he stabbed him with many wounds before he had time to put himself on his guard; then killing a sentinel, he escaped in the darkness. He adds- “Some say the traitor was hired by the Covenanters to do this ; others, only that he was promised a reward if he did it” – the distinction seems rather a fine one. “However it was, this is most certain, that he is very high in their favour unto this very day; and that Argyle immediately advanced him, though he was no soldier, to great commands in his army.” And he concludes with a touching account of Montrose’s tribute to his dead friend ¬ “Montrose was very much troubled with the loss of that nobleman, his dear friend, and one that had deserved very well both from the King and himself; a man famous for arts, and arms, and honesty; being a good philosopher, a good divine, a good lawyer, a good soldier, a good subject, and a good man. Embracing the breathless body again and again, with sighs and tears he delivers it to bis sorrowful friends and servants, to be carried to his parents to receive its funeral obsequies, as became the splendour of that honourable family,”1

The family account is to the effect that Stewart was not a subordinate of Kilpont, but in an independent command; and through his intimacy with Kilpont he had induced the latter to join the royalist cause. The Irish levies, when coming from the west under the command of Colkitto, had plundered the lands of Ardvoirlich, and of this Stewart complained to Montrose, but obtained no redress. ‘He then challenged Colkitto and Montrose, on the information and advice of Kilpont, it is said, put both under arrest and then patched up a sort of reconciliation. But Stewart was far from being satisfied; and after the banquet, when the friends had returned to their tent, he broke out into fierce reproaches again. both Kilpont and Montrose. Kilpont replied also in high words. From words they went to blows, and Stewart, who was a man of great strength, slew Kilpont on the spot. He fled after the deed and, for his own safety, was obliged to throw himself into the hands of the Covenanters.2 This account frees Ardvoirlich from the accusation of treachery to Montrose, though it represents him as a man of violent temper.

The Act of Parliament narrates that John, Lord Kilpont, being employed in the public service against James Graham, then Earl of Montrose, the Irish rebels and their associates, did treacherously and treasonably join himself and induce

1 Wishart’s Commentaries on the Wars of Montrose, quoted by Sheriff Napier in hi sMemoirs of Montrose, ii. 446

2 Legend of Montrose, Postscript to Introduction (edit. 1829)

400 others under his command to join the said rebels ; that Stewart and some of his friends, repenting of their error, resolved to forsake their wicked company, and imputed this resolution to Kilpont, who endeavoured, “out of his malignant dispositione,” to prevent them, and fell a struggling with the said James, who, for his own relief, was forced to kill him, along with two Irish rebels who resisted his escape; and that then, with his son and friends, he came straight to the Marquis of Argyle and offered their services to the country.’

The particulars in this narrative would in all probability be supplied by James Stewart himself, and they seem, in every point, to contradict the family tradition. No mention is made of the plot to murder Montrose ascribed to him by Wishart, but in other respects the account of that writer is confirmed. He tried, according to this statement approved by himself, to make Kilpont false to the cause of the Royalists, and killed him when he did not succeed. It is quite possible that the statement may be not altogether ingenuous, as he might suppose that his zeal for the Covenant would be likely to condone the offence of killing one of its enemies. But if not accepted as it is, the plot to assassinate Montrose must still stand on a footing of at least equal authority with the grievance against Colkitto as the cause of the quarrel which ended so fatally.

1 Acts of the Parliament of Scotland, vol. vi. pt. i, p. 359 (1st March 1645)

The Murder of Lord Kilpont

A murder during Montrose´s campaign in 1644

by Jenn Chamberlain, Stewart Society Archivist.

Click here for the original article.

Montrose raised the Royal Standard at Blair Atholl on the 30th of August, 1644, . As the Royalists approached the valley of the Earn they were intercepted near Buchanty by a force of 400 bowmen under the command of Lord Kilpont, accompanied by John Drummond (a younger son of the Earl of Perth), the Master of Madertie (Montrose’s brother in law), and James Stewart of Ardvorlich with his son Henry. Kilpont, who was unaware of Montrose’s arrival in Scotland, had been summoned by the local Covenanting authorities to muster his men to oppose the Irish under the command of Alastair Mac Colla.

As the eldest son of William Graham, Earl of Airth and Menteith, the most important of the Graham cadets, he was related to Montrose and, having seen the King’s commission, he willingly brought his men over to join the Royalists. Kilpont’s force subsequently fought with distinction at Tippermuir the following day. Montrose’s army suffered many wounded but only one Royalist is said to have been killed outright on the battlefield. However, Henry Stewart, Ardvorlich’s son, was mortally hurt in the fight and died of his wounds a few days later.

During the early hours of the morning of 5th September a commotion broke out in the Royalist camp. Assuming that a quarrel had broken out between the Irish soldiers and the local highland troops. Montrose and his officers drew their swords and rushed towards the centre of the disturbance. There they found the body of Lord Kilpont who had been stabbed to death only a short time before. The murderer was known to have been James Stewart of Ardvorlich, who had also killed two Irish sentries when they tried to prevent his escape. The crime was the more terrible in that Kilpont had been Ardvorlich’s closest friend.

As a young man he was befriended by Lord Kilpont (they were distantly related) and the two became virtually inseparable. They regularly slept in the same room together and on the night of the murder they were sharing a tent. It is possible they were lovers.

The Royalist account of the murder, published shortly afterwards in a pamphlet entitled ‘A True Relation of the success of His Majesty’s forces in Scotland under the conduct of The Lord James, Marquis of Montrose……..’, suggested that Ardvorlich’s true intention had been to assassinate Montrose himself:

‘While he was on his march, one morning by the break of day, Captain James Stewart did withdraw the Lord Kilpont to the utmost Centry where he had a long and serious discourse with him; at the end whereof, my Lord (Kilpont), knocking upon his breast, was overheard to say these words, “Lord forbid man; would you undoe us all?”, upon which immediately the Captain stob’d him with a durke, and my Lord falling with the first stroke, he gave him fourteen more through the body as he lay upon the ground; that he might be sure as is probable that he should not reveal what had passed between them; for it is conceived that he had intended so much for the Marquisse (Montrose), and that he had disclosed his purpose to my Lord Kilpont (whom) he thought to have engaged in the plot in regard to the familiarity (that) was between them. After the villain had committed this barbarous act, he came to the Centry and shot him through the body and so by reason of a thick fogge, made an escape to the Rebells, of whom he was well received’.

The account of the affair handed down in Ardvorlich’s family, however, ascribes James Stewart’s motive to a deep-seated grudge which he had conceived against Alastair MacDonald. According to this version the Irish soldiers, during their earlier wanderings prior to linking up with Montrose, were said to have pillaged some lands belonging to Ardvorlich who, shortly after joining the army at Buchanty, made a formal complaint to the King’s Lieutenant. It seems that Montrose, possibly because of his anxiety to conciliate his new allies rather than to judge between them, returned an evasive answer which so dissatisfied Ardvorlich that he became angry and challenged Alastair to single combat. Before they could meet Montrose, acting it is said on the advice and information of Lord Kilpont, placed both men under arrest until they should become reconciled. They were eventually persuaded to shake hands in his presence, which they did with an ill grace, and Ardvorlich gripped Alastair’s hand so hard as to cause the blood to start from under his fingernails. Stewart however was still very dissatisfied. According to this version, as told to Sir Walter Scott in 1830 by Robert Stewart of Ardvorlich.

‘A few days after the battle of Tippermuir, When Montrose with his army was camped at Collace, an entertainment was given by him to his officers in honour of the victory he had obtained, and Kilpont and his comrade Ardvorlich were of the party. After returning to their quarters, Ardvorlich, who seemed still to brood over his quarrel with the MacDonald, and being heated with drink, began to blame Lord Kilpont for the part he had taken in preventing his obtaining redress, and reflecting against Montrose for not allowing him what he considered proper reparation. Kilpont defended the conduct of himself and his relative Montrose till their argument came to high words; and finally, from the state they were both in, by an easy transition, to blows, when Ardvorlich with his dirk struck Kilpont dead on the spot’.

This version of the story was said to have been drawn from the account of John dhu Mhor, a natural son of Ardvorlich, who was also with his father at Collace and may thus have actually witnessed the murder. John dhu Mhor lived until after the revolution and passed the story on to his grandson, who told it to the father of Sir Walter Scott’s informant.

It does not ring altogether true however for two reasons. Firstly, the Clanranald MS gives an account (often quite detailed) of Alastair’s movements between the time of his landing in Ardnamurchan and his meeting with Montrose at Blair Atholl, and there is no record of the Irish soldiers having pillaged in the neighbourhood of Ardvorlich’s lands prior to Tippermuir. They did burn Ardvorlich as a reprisal for the murder the following year (1645) shortly before the battle of Auldearn. Secondly, given Alastair’s own fiery temperament and his standing among the Irish, it is unlikely that Montrose would have risked actually putting him under arrest. What is interesting about this family version of the affair is the suggestion that the pillaging of Ardvorlich’s lands or property may have had some sort of bearing on it. (It is equally strange perhaps that none of the accounts refer to the death of his son only a few days previously as a factor which may have affected his state of mind).

There are however two letters written by the Marquis of Argyll to John Campbell the Younger of Glenorchy and dated 4th and 5th of September – that is, the day before and the day of the murder. Argyll had received the news of Tippermuir and was in the process of mustering an army to pursue Montrose. He was also initiating a long investigation into the cause of the disaster, while his officers were instructed to discover precisely who had joined or assisted Montrose, and upon what occasion. In the first letter of 4th September Argyll told Glenorchy that he: ‘….may medle with the goods of James Stewart of Ardvorlich for it is more reasonable to secure the goods of those who entertained the rebels than those of honest men’.

The second letter, while ordering Glenorchy to punish by death any troops found guilty of plundering, robbery, or other disorders, then instructed him to march towards Glenalmond ‘carrying Ardvorlich’s goods along’. Considering that Argyll was meticulously drawing up a list of all those who had helped Montrose – which, after Tippermuir included a number of the local gentry such as Kilpont, Drummond and Madertie, – it is strange that only Ardvorlich should have been mentioned by name in Glenorchy’s instructions. Indeed, he was singled out for special treatment. It is also odd that an army marching to pursue Montrose should have been ordered to encumber itself with Ardvorlich’s goods when these could more sensibly have been deposited safely in Glenorchy, Inveraray, or some other suitable place. It is almost as if Ardvorlich was to be confronted with his own plundered goods.

This indeed may well have been Argyll’s purpose. Something had made him decide that Ardvorlich should be singled out and special pressure brought to bear on him. Pressure implies a threat, but a threat, if it is intended to be effective, precedes the act. In other words, Argyll’s tactic was not just to raid Ardvorlich’s lands but also to make sure that Ardvorlich knew that it would happen. If this sequence is logical and correct then given that the first order to Glenorchy was sent on 4th September, the threat was made between Ardvorlich’s joining Montrose’s army on 31st August and that date – all of which points to some sort of exchange having taken place while the army was in Perth. By the 4th September Argyll, unaware of just how effective the pressure was proving, was ready to carry out the threat (of pillaging Ardvorlich’s lands) and ensure, by having the plunder brought with the army, that Ardvorlich got to hear of it.

It was more likely therefore that it was Argyll, and not Montrose or Alastair, who triggered the tragic murder of Lord Kilpont. Of we cannot be sure what Ardvorlich was being forced to do, whether merely to desert Montrose, or to murder him or to find a means of betraying the army. Ardvorlich himself, already fragile because of the death of his son and now likely to lose land wealth and cattle as well, possibly decided to accede, and told Kilpont he was going to do so. Kilpont was horrified, but before he could reveal anything of the conversation Ardvorlich, despairing and possibly drunk, killed him. The fourteen stab wounds in the body suggest something of a frenzy.

After the murder Ardvorlich had little choice. He joined Argyll (who wrote no more about the plunder) and was made a Major in his regiment. The Covenanters praised him for the deed and made what propaganda they could out of it. ‘Kilpont’s treachery is avenged by his death justly inflicted’ wrote one minister, and when in 1645 the Scottish Parliament formally ratified Ardvorlich’s ‘pardon’, it was stated that he had been entirely justified in his action: ‘………heartily therefore repenting of his error in joining with the said rebels, and abhorring their cruelty, (Ardvorlich) resolves with his said friends to forsake their wicked company, and imparted this said resolution to the said umquhile Lord Kilpont. But he, out of his malignant disposition opposed the same, and fell in struggling with the said James, who, for the sake of his own relief, was forced to kill him at the Kirk of Collace, with two Irish rebels who resisted his escape, and so removed happily….and came straight to the Marquis of Argyll and offered his service to his country. Whose carriage in this particular being considered by the Committee of Estates, they find and declare that the said Stewart did good service to the Kingdon in killing the said Lord Kilpont…. And approved of what he did therein’. (Acts Parlt. Scot. V1. pt. i 359).

Argyll’s reception of Ardvorlich was no doubt intended to encourage others to similar action, and on 12th September, as a logical sequel, the Committee of Estates offered a bounty of £20,000 to anyone who would assassinate Montrose.

Many of the weapons used by James Stewart are still at Ardvorlich House now including the dirk used to murder Kilpont.

Lord Kilpont was the eldest son of the William Graham, 7th earl of Mentieth and was born about 1613. In April 1633 he married Lady Mary Keith, daughter of William, 6th earl Marischal. They had a son and three daughters.

He was buried in the family´s mausoleum in the old chapter house of the priory of Inchmahome, on Inchmahome Island in the Lake of Menteith which the Society now owns. There is no plaque or any other marker to his memory. The site of his grave is covered by another tomb monument from another period, moved some years ago.

James Beag Remains Loyal to his Fellow Stewarts

As noted above, during the First Covenanting War of 1644-45, initially, James Beag, like all the other Highland Stewart clans, supported King Charles I, under the generalship of James Graham, Marquis of Montrose. After the murder of John Graham, Lord Kilpont, James Beag Stewart was forced to “turn his coat,” flee Montrose’s army, and join the Covenanter army under General David Leslie, or face certain execution. He was rewarded with a Major’s commission and hailed as a hero by the Covenanter army. Yet, his subsequent actions under General David Leslie (on the Covenanter side) reveal that his true deeper loyalties remained with the Stewarts.