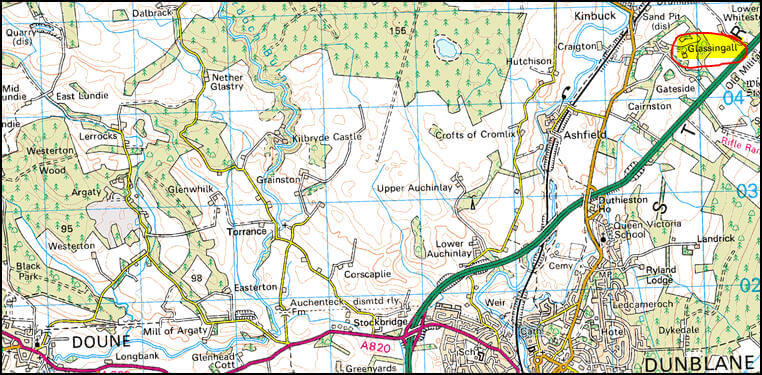

The Stewarts of Glassingall, Dunblane, Perthshire, Scotland

Descendant Line IVb of the Stewarts of Annat

The Stewarts of Glassingall are a descendant line of the Stewarts of Lendrick who are cadet branch of the Stewarts of Annat. Like many of the Annat branches, the Stewarts of Glassingall were heavily involved in the Jacobite Uprisings of 1715 and 1745. They seem to have been especially involved in the secret plotting for the 1745 Uprising.

Glassingall was one of the residences visited by James Stewart of the Glen and Alan Breck Stewart on their travels prior to the Appin Murder. This story was later romanticized by Robert Louis Stevenson in his novels, Kidnapped and Catriona, which were subsequently made into a film starring Michael Caine. The fictional estate of Shaws featured in the story is based on Glassingall, and the lead character, David Balfour, is based on Thomas Stuart Smith, a descendant of the Stewarts of Glassingall (found at the bottom of this page).

The Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856)

The estate of Glassingall was embroiled in a large ultimus haeres (ultimate heir) legal dispute in the mid-19th century that lasted for six years when it’s occupant, Alexander Smith, a descendant of the Stewarts of Glassingall, died intestate and without a designated heir. Alexander’s late uncle, Archibald Stewart, 2nd of Glassingall, upon his earlier death without children had stated in his will that, upon the failure of any descendant line, the estate of Glassingall should revert to the closest Stewart family. Alexander Smith, like his uncle, also had no children and his older brother, Thomas, had only one son who was illegitimate. Multiple Stewart claimants, all of whom were descendants of the Stewarts of Annat, as well as others, came out of the woodwork attempting to lay claim to the Glassingall estate. Each of these claimants provided a thorough family tree to back up their claim of right to inherit Glassingall. These trees contradict each other in small, but significant ways, as each claimant had a financial motive for positioning themselves as being the closest living relative to the extinct Stewarts of Glassingall. However, despite these biased contradictions, a studious comparison of all the trees taken together has allowed us to present a more thorough and accurate accounting of this branch than might otherwise have been possible. We are indebted to the work of Ailsa Gray of Glassingall in uncovering and helping to analyse the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856).

Sources

In our research, we cite many documentary sources. Some of the most common ones that you will find referenced and abbreviated in our notes include:

- Duncan Stewart (1739). A Short Historical and Genealogical Account of the Surname Stewart…. (It’s actual title is much longer), by Rev. Duncan Stewart, M.A., 1st of Strathgarry and Innerhadden, son of Donald Stewart, 5th of Invernahyle, published in 1739. Public domain.

- Stewarts of the South. A large collection of letters written circa 1818-1820 by Capt. James Stewart, factor (estate manager) to Maj. Gen. David Stewart of Garth, comprising a near complete inventory of all Stewart families living in southern Perthshire, including all branches of the Stewarts of Balquhidder.

- MacGregor. The Red Book of Scotland, by Gordon MacGregor, 2020 (http://redbookofscotland.co.uk/, used with permission). Gordon MacGregor is one of Scotland’s premier professional family history researchers who has conducted commissioned research on behalf of the Lord Lyon Court. He has produced a nine volume encyclopedic collection of the genealogies of all of Scotland’s landed families with meticulous primary source references. Gordon has worked privately with our research team for over 20 years.

- [Name] OPR. This refers to various Old Parish Registers.

- FOR A FULL LIST OF SOURCES CLICK HERE.

“I have seen wicked men and fools,

a great many of both;

and I believe they both get paid in the end;

but the fools first.”

―

Glassingall

Glassingall is an estate in Dunblane parish, Perthshire, Scotland, northeast of the town of Dunblane. The estate house is a Georgian laird’s house, built in 1745. It is famous for being the house portrayed as the fictional House of Shaws in the novel, Kidnapped, by Robert Louis Stevenson.

“In 1778, a farmer on nearby Glassingall estate called Michael Stirling invented one of the first threshing machines which revolutionized agriculture in Scotland. This estate, once owned by the strongly Jacobite Stewart family, descended through them to two brothers called Alexander and Thomas Smith who inherited it in 1802. They both fell in love with the same girl and she eloped to London with Thomas. She died there giving birth to a son called Thomas. (sic – She died when Thomas was a young boy. He had young childhood memories of his mother.) The boy’s father drowned in Cuba and young Thomas had the greatest problem proving his identity as there was not a scrap of paper to prove who he was.

“He managed to establish contact with his uncle Alexander who provided funds to allow the boy to study art in Rome (sic – Naples). Then his uncled died in 1849 without leaving a will and his nephew had enormous difficultuy obtaining his rightful inheritance. Robert Louis Stevenson heard this story while holidaying at Bridge of Allan, and from it modelled the plot of his famous novel Kidnapped, in which Thomas Smith junior became David Balfour (sic – His correct name was Thomas Stuart Smith. He was actually the third Thomas Smith in the family, so his father was technically Thomas Smith, Jr.), and his uncle Alexander became Ebenezer Shaw (sic – Ebenezer Balfour of Shaws). It will be remembered that all of David Balfour’s problems were due to his father and uncle loving the same girl. Thus the real-life “House of the Shaws” was Old Glassinghall House, recently restored eighteenth-century laird’s house. Thomas Smith junior (sic – Thomas Stuart Smith) left funds (as well as his entire art collection) in his will for the building of the Smith Institute in Stirling, now a flourishing and prize-winning museum and art gallery.”

— (McKerracher, Archie. Perthshire in History and Legend. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers, 1988, p. 160-161)

Origin of the Stewarts of Glassingall

The Stewarts of Glassingall descend from Archibald Stewart, youngest son of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Annat. Duncan Stewart (1739) says “Alexander, who purchased the lands of Annat… had John, Walter, Andrew and James. He had likewise Archibald, great-grandfather to Alexander Stewart of Glassingall, writer in Stirling.” From this, we can determine that Alexander Stewart of Glassingall, who was alive in 1739, was the great-grandson of Archibald Stewart, younger son of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Annat.

Stewarts of the South does not mention the Stewarts of Glassingall as that family had become extinct in the Stewart line by 1820. The estate of Glassingall had passed to a nephew through a daughter line, namely, Alexander Smith, by that point. Stewarts of the South gives us an accounting of the Glassingall parent family, the Stewarts of Lendrick, which can be found on our Stewarts of Lendrick page.

The Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856) provide us with valuable information on all the generations of the Stewarts of Glassingall.

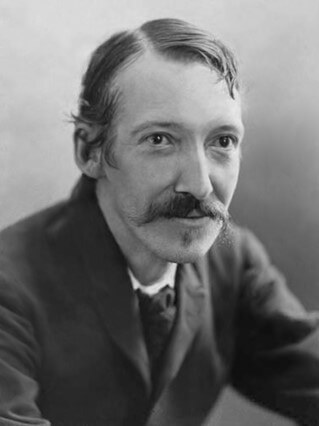

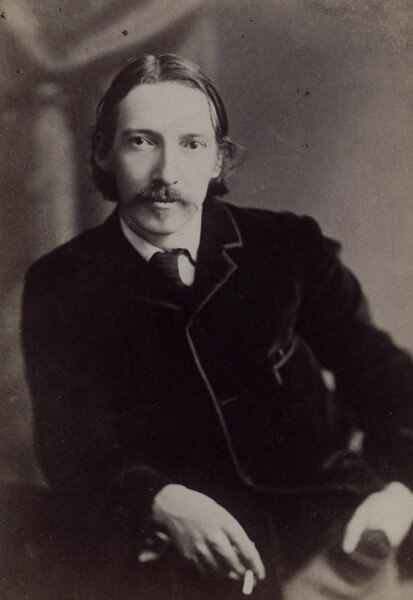

Robert Louis Stevenson and the Stewarts of Glassingall

Robert Louis Stevenson was a 19th century Scottish novelist best known as the author of Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. He also wrote Kidnapped and it’s sequel, Catriona, which were later made into a 1971 movie staring Michael Caine. These books tell the story of a fictional character, David Balfour of Shaws, who gets caught up in a Highland murder case, based on the real life Appin Murder involving James of the Glen and Alan Breck Stewart. In the book, Davie is trying to reclaim his family estate of Shaws, wrongly swindled from his late father by his corrupt uncle. The character of David Balfour is based on the real life story of Thomas Stuart Smith (1807-1869), a descendant of the Stewarts of Glassingall (shown below), and his real life battle to claim the estate of Glassingall from the Crown after his uncle, Alexander Smith of Glassingall, died intestate. The 19th century legal case surrounding his claim provides us with a wealth of information in the Glassingall Court of Session Papers.

David B. Morris, clerk of the Town of Stirling, author of Robert Louis Stevenson and the Scottish Highlanders (Stirling: Eneas Mackay Publishing, 1929), wrote about various Jacobite families involved in the Appin Murder and whose escapades inspired the books Kidnapped and Catriona.

The Stewarts of Glassingall

(pp. 32-37, subheadings and corrections added.)

The Opening of Stirling to the Jacobites

Another family of Stewarts lived at Glassingall, a pleasant estate on the Allan Water about a mile north of Dunblane. The old town house of the Glassingall family still stands in the Broad Street of Stirling. Its rooms adorned with painted panels. Archibald Stewart of Glassingall was cited as a witness at the trial of James Stewart, but was not called. What his part in the drama was we cannot say, but he was an earnest Jacobite. Janet Stewart of the Glassingall family, was either the wife or the mother of John Jaffray (sic – she was his wife, see below), who in the momentous years 1745-46 was a Bailie, and acted as Provost of Stirling in place of the elected Provost, who had declined office. Jaffray was afterwards Provost in his own right. When Prince Charles was retreating north after his incursion into England, he resided for a short time at Bannockburn House, from which he sent a letter to the Town Council of Stirling, calling upon them to surrender the place. The walls of Stirling were then intact, there was a strong garrison in the Castle, and for the defence of the town the citizens were in arms. Under General Blakeney, the guards were posted, and it was intended to bid defiance to the Prince and his Highlanders. but somehow the people changed their minds, the gate was opened, and the Jacobites entered and took peaceful possession of the town, although not of the Castle. How this happened was not quite clear, but the local tradition is that Provost Jaffray, under the influence of his Stewart wife, (or mother) (sic), arranged the matter. There can be no doubt that the Prince had many sympathisers among the citizens. The circumstances under which the Jacobite army entered Stirling were the subject of a great deal of comment at the time. The St. James’ Evening Post made some very caustic comments, which caused the Town council to compile a full account of the transaction, which they engrossed in their Minute Book.

The Love Triangle of Glassingall

In the end of the eighteenth century the grandsons of Provost Jaffray, Alexander Smith and his brother Thomas were the joint owners of Glassingall, Both loved the same lady. When she chose the younger (sic – other versions of the story state that Thomas was the older brother and that Thomas gave up his interest in Glassingall in exchange for Alexander withdrawing interest in the woman), the brothers quarrelled and never spoke to each other again. Alexander took the matter so much to heart that he remained true to his early love and never married. Thomas and his bride went to the continent, where she died at the birth of her son, or soon after. The boy was left in the care of a French schoolmaster, and the father went to Cuba, where some years later he was drowned. As the boy grew older, an effort was made to trace his relatives, and ultimately a letter was sent to his uncle Alexander. Thomas Stewart Smith fared better than David Balfour did with his uncle Ebenezer, for Alexander Smith made an annual provision for his nephew which enabled him to enter on his career as an artist. When Thomas was a man entering on middle life, Alexander died, and as no will could be found, the Crown took possession of Glassingall and the rest of the property. Thomas Stewart Smith encountered the utmost difficulty in establishing his claims. It was an extraordinary circumstance that he did not know the date or the place of his own birth, or where or when his father and mother were married, or even his mother’s maiden name. And so began a search over the length and breadth of Europe for a missing birth certificate and missing marriage lines. All efforts were fruitless, but ultimately the Crown authorities were satisfied, and Thomas, like David Balfour, came into his estates.

The Smith Institute

Thomas Stewart Smith sold Glassingall, and directed the proceeds to be applied to the erection and maintenance of the Smith Institute in Stirling. This is a museum and picture gallery containing a very fine collection of paintings, mostly gathered together by the founder, who was on intimate terms with the leading artists of his day in this country and on the continent.

The Connection to Kidnapped

Stevenson was probably quite familiar with the Smith Institute, which was erected and opened during his Bridge of Allan days, (In fact, Robert Louis Stevenson visited the Smith Institute when it opened.) and he must have heard the romantic story of the two brothers falling in love with the same lady. He introduced this theme in Kidnapped. The true origin of all David Balfour’s trials and misfortunes lay in the fact that his father and uncle both loved the same woman, and in the extraordinary arrangement made by the brothers under which the one secured the bride and the other took the estate, while they parted never to meet again. A similar idea forms the leading motive in [Robert Louis Stevenson’s] The Master of Ballantrae, which also is a Jacobite story. There, too, is a lady loved by two brothers, who quarrel, and an estate, the possession of which is an added cause of bitterness.

Predecessors to the Stewarts of Glassingall

Archibald Stewart, Predecessor of Lanrick and Glassingall, b. Abt 1595, Annat, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN. Archibald was the youngest son of Alexander mac Iain Stewart, in Glen Finglas 2nd of Portnellan and 1st of Annat, He was father of:

, d. UNKNOWN. Archibald was the youngest son of Alexander mac Iain Stewart, in Glen Finglas 2nd of Portnellan and 1st of Annat, He was father of:

-

- John Oig mac Gillespic Stewart, in Lanrick? (speculative), b. Abt 1620, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 1662, Lanrick, Callander, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 1662, Lanrick, Callander, Perthshire, Scotland  (Age ~ 42 years). He was father of:

(Age ~ 42 years). He was father of:

- Capt. Archibald Stewart, in Annat, b. possibly abt 3 Jan 1647, Annat, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 10 Jul 1732, Annat, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 10 Jul 1732, Annat, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland  (Age ~ 85 years), who married Helen Law. They were parents of:

(Age ~ 85 years), who married Helen Law. They were parents of:

- John Stewart, 1st of Ballacuaich and Lendrick, b. Abt 3 Nov 1680, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 1740, Lendrick, Callander, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 1740, Lendrick, Callander, Perthshire, Scotland  (Age ~ 59 years).

(Age ~ 59 years). - Alexander Stewart, 1st of Glassingall, b. Abt 17 May 1685, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 22 Jul 1742, Glassingall, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 22 Jul 1742, Glassingall, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland  (Age ~ 57 years).

(Age ~ 57 years). - additional children

- John Stewart, 1st of Ballacuaich and Lendrick, b. Abt 3 Nov 1680, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland

- Capt. Archibald Stewart, in Annat, b. possibly abt 3 Jan 1647, Annat, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland

- John Oig mac Gillespic Stewart, in Lanrick? (speculative), b. Abt 1620, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland

Detailed information on the predecessors to the Stewarts of Glassingall can be found on our Stewarts of Lendrick page:

Alexander Stewart, 1st of Glassingall, maltman, law clerk, and Jacobite financier

Alexander Stewart, 1st of Glassingall, b. Abt 17 May 1685, Kilmadock, Perthshire, Scotland  , d. 22 Jul 1742, Glassingall, Dunblane, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. 22 Jul 1742, Glassingall, Dunblane, Perthshire, Scotland  (Age ~ 57 years). Alexander was the second son of Capt. Archibald Stewart in Annat, shown above.

(Age ~ 57 years). Alexander was the second son of Capt. Archibald Stewart in Annat, shown above.

Alexander married to Helen Fleetwood, b. Abt 1690, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

Duncan Stewart (1739) mentions this Alexander as the great-grandson of Archibald Stewart, son of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Annat, in the following reference: “Alexander, who purchased the lands of Annat from James Muschet of Burnbank anno 1621. He married ___ MacNab, daughter to Aucharn, by whom he had John, Walter, Andrew and James. He had likewise Archibald, great-grandfather to Alexander Stewart of Glassingall, writer in Stirling.”

Register of Baptisms 1685 (1684?) May 17th Alexander son to Archibald Stewart and Helen Law in Annat witness Alexander Stewart and Charles Stewart, Extracted from the Parish records of Kilmadock this 25 June 1851 (The witnesses in this case, would be Alexander Stewart of Annat and his younger half-brother, Charles Stewart.)

Alexander is recorded in the later Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856) as “Alexander Stewart, the first proprietor of Glassingall, Bents and Lochend. He died about 1742.” He is shown as the son of Archibald Stewart “of Annat” (sic) and the younger brother of John Stewart of Ballacauich and Lendrick. Alexander purchased Glassingall and Bents (Banks?) in 1724 and Lochend in 1731. The 1650 Valuation Roll for Dunblane Parish shows Glassingall partially possessed by Mr James? Drummond at that time.

Alexander was a maltman and writer (law clerk) in Stirling. He was the great-great-grandson of Alexander, 1st of Annat. He married Ellen Fleetwood, daughter of John Fleetwood, merchant and maltman in Stirling. In 1716 Alexander was himself admitted as a maltman burgess and guild brother. He and his wife acquired considerable property in the Middle Bow (Glassingall House at 30 Bow Street), Castle Wynd, and Meal Market, that is King Street and in East Craigs, Stirling, and also the lands of Bents and Lochend.

Alexander is also recorded in the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856) as being an “agent” for Prince James Francis Edward Stuart, the Old Pretender, during the Jacobite Risings of 1715 and 1719. He owned the estate of Glassingall which was in the heart of Jacobite territory as well as a townhouse in Stirling, which was Whig country, loyal to the Hanovarians. This allowed him to move freely between both places.

“Muschet sold Glassingall land to Alexander Stewart. The house I think had been burned down after 1715 and Muschet fled to Ireland a fugitive for allowing the Jacobite army to camp on his land. When Glassingall was bought by Stewart (about 1726) it looks as though Muschet tried to resist, but Stewart insisted, calling in some debt that Muschet owed him. Glassingall, as a location, was clearly strategic and desired by the Stewarts. This Alexander Stewart was the ‘agent’ of the Stewart Clan.” — Ailsa Gray of Glassingall

According to research conducted by Ailsa Gray of Glassingall (2022), Alexander died with £15,000 in debts owing to him. (Approximately £500,000 in 2022, or $600,000 USD, $750,000 CDN, or $900,000 AUS.) The debtors were all prominant Jacobites whom he had made no effort to collect from. The implication being that these were not actual loans but that Alexander was in fact funnelling money to Jacobite leaders, possibly from external sources.

“Alexander Stewart was succeeded in Glassingall by his only (surviving) son, Archibald, who completed title in 1748. The only (surviving) sister of the latter, namely Janet, married Baillie John Jaffrey, merchant in Stirling and afterwards Provost of Stirling. After owning Glassingall for about 30 years, Archibald Stewart conveyed the property to Alexander Jaffrey, merchant in Stirling, his nephew.” (Alexander Barty, The History of Dunblane, c/o Belinda Dettman)

The Will of Alexander Stewart (1st of Glassingall)

Inventory of Debts resting to the deceased Alexander Stewart writer in Stirling, time of his death which happen upon the 22nd of July 1742 made given up by Archibald Stewart the deceased’s son who has in ……..nominal by his father by disposition of the date the 20th of July ….., with consent of a Helen Fleetwood his mother, Alexander Stewart [4th] of Annet, Robert Rollo from the Clark of Clackmannan, John Jaffray and John Burd…in Stirling and Robert Leckie ………Archibald Stewart by the foresaid Disposition.

By James Forsyth of Garvald for bill dated 8th November 1736 payable at land 1737 £400

By Ensign James Menzies of the Grants Regiment of Foot for bill payable 25 May 1712 £10.12

By Capt Mackie to promise a note dated 12th October 1722 payable on demand.

By William Paterson in Easter Frew for … bill dated 5 December 1740 payable at hand 1741

By George Robertson in Bankhead of Denny and Andrew Adam in … Haugh for a …as remains of a bill dated 2 July 1730 par 255 ..month as the remains…

By John Graeme …of Carnoch for bill 24 Febraury 1733 payable on demand.

By James Stuart … in Stirling for bill dated 24 July 138 payable 24 March.

By John Gordon of Kirkconel late Collector of …for bill 30 December 1731 payable …. 1732

By David Dun in Easter Crinzel ///no;; dated to last of …1735 payable at Mar year after.

By Robert Ewing tenant in Garvelland called Horthshiels of Dennygreen for bills dated 12 July 1742 payable at three different times.

By Walter Craig Copperforth in Stirling for bill dated 20 Sept 1736 payable 14 dates after death.

By David Din late servant to the deceased for bill dated 20 November 1741 payable the 1st December year after

By James Geddes in Bilston in the parish of Livingston for bill 11th September 1706 payable the 21st October year after protested for non-payment.

By Andrew Chalmers weaver in Stirling for bill dated th August 1726 available at two terms.

By George Clelland of Tasker at Bonnywater and John Rankin in Rolenstocks Connelll Sealyplace dated May 1717 payable by the 17th said month.

By James Craeme County keeper in Northumberland for bill 11 July 1719 payable the 1st August year after.

Mr John Graeme of McKeanston for bill 10 November 1724 payable at land 1725

Mr Thomas Rob in Auchenbowie and Thomas Rob his son for a bill Connel Sealy bill 3 December 1734 payable the 9th of month.

By Janet Dun relict of William Dun from Gatearron (Gartacharn?) for bill dated February 145 indexed to the deceased and payable at …year after protested.

By Lord Rollo for bill 20 June 1715 payable 1st August year after.

By David Din in West Crinzel for bill 29th December 1722 payable 1 June 1723

By James Laing tenant in Barton for bill 7th March 1735 payable at Tambas year after

By James Ure in quarter of Fintry for bill 12th March payable on demand.

By James Allan Wright of Alloa payable 10 January 1738 payabel at land said year

BY Archibald Douglas of Garvel for bill 20 May 1734 payable 13 June year after

By William Drummond at Airthreysmile for bill 9 June 1739 payable 8 days after date.

By Agnes Miller relict of Laurence Keir …in Stirling for bill 13 July 1725 payable at …year after

By James Christie in Shanhead? Of Gartarron (Gartacharn) for bill 3 May 1733 payable 23 said month …

By David Gillespie …in Stirling for bill the 11December 1740 payable on demand.

By Geo Henderson, …weaver in …hill for bill the 20 Sep 1731 payable ….

By William Garner of Wester Ba…for bill …1731 payable 22nd said month.

By John Duncan in Bandeath for bill 27 December 1721 payable 22 February year after.

By James Rennie parish of St Ninians for bill 22nd May 1842 payable the first of June year after.

By James Din late…for bill 26 May 1730 payable on demand.

By Archibald Anderson banker in Stirling for bill 12 February 1720 payable 1st March year after.

By John Campbell Maltman in Stirling for bill 26 September 1732 payable at … 1733

Mr Andrew Buchanan in Balochnech for bill 7 July 1730 payable 5 days after date

By James Main … in St Ninians for bill 6th August 1728 payable on demand.

By William Cruickshanks…in Aberdeen for bill 24 August 1745 payable on demand.

By Lieutenant Alexander Stewart of Col Halketts Regiment of Foot for bills 11 June 1731 drawn by the …payable to William Christie stabler in …

By George Morris Guner in Stirling Castle for bill 7 May 1733 payable at Lambas year after

By Robert Anderson in Craigside of Plean for bill 13 June 1739 payable …days after date

By Andrew Wood, brewer in Stirling for bill 11 December 1727 for Scots payable on demand and the sum of £190 money for of another bill dated April 1720 payable 10th of month upon which he is …diligence both sums.

Mr Charles Thomson in Dunblane for bill 20 September 1733 payable at …1734

By John Ferguson, Customer at Stirling Bridge for bill 7 July 1740 payable 3 days after date

By James Buchanan Merchant at Bridgend of Dunblane for bill September 1722 payable …

By James Stevenson flesher in Stirling for bill 3 August 1725 payable the first September thereafter.

By Robert Buchanan son to Robert Buchanan of Provanstown for bill July 1719 payable the tenth of the month

By John Graeme Blaircessnock for bill dated 13 June 1721 payable in manor mentioned in said bill.

By Robert Meiklejohn…. In Dunblane for bill 24 November 1729 payable at …year after

By John Livingston, Glazier in Stirling, for bill 12 January 1722 payable 26 said month

By William Stewart, merchant in Crieff for bill 26 …1736 payable …thereafter

By Donald Stewart for bill dated 26 1736 payable five months after date

By Robert Stirling, dyster at Bridge of Stirling for bill dated 1 …1725 payable 15 of month

By William Hendry of Lochridge for bill 18 May 1723 payable at …year after.

By William Gordon, junior to Merchant in D…. for bill 19 December 1710 payable at Lambas 1711 to John Stewart, Junior Writer to the Signet and find owed by him to the defunct for …

By Gilbert Brown write in D (same place as above) for bill November 1724 payable 20 th of month £15 Scots sent from at …………………

By James Ure in quarter for bill 5th December 1741 payable 10 days after date.

By William Stewart and James Cock, merchants in Grey Connello Seally, as remainds of a bll 5th May 1733 payable ….of June year after

By John Ewing in Ia…of Fintry for bill 27 January 1725 payable at Ma…year after

By John Ewing in Lag of Fintry for bill in Nov 1729 payable at lan…year after.

By John Miller, Mason in Stirling for bill…….to the fecunt dated 5 January 1740 payable at …land year after.

By John Din, son to William Din in Allanhead of Campsie for bill to the defunct dated 8 June.

By William Henry Allan, Merchant and Wright in Stirling for bill …to the defunct dated …..1724 payable the 19 April year after

By John Davie, Burgess of Stirling and Robert Hamilton at Raplochburn (Connell and Sealy) for bill 13 December 1734 payable at land 1735

By Hugh Jeffrey, Merchant in Cambusbarron for bill 22nd December 1721 payable on demand.

By William Moirson in Bandeath and Geroge Morison son to George Morison in M…Conny and Saly for bills 13 Apilr 1724 payable at Lambas

By Archibald Angus, parish of Bankeir and Jo Gray write at Dennykirk Coully and Seally for bill 22 December 1727 payable at land 1720 remains due

By David Din in East Grinzel, George Din in …haugh and Willim McKillian parish of Clachary Coully o Seally for Bill 11 June 1720 payable 21 December

By George Rind, m….in Stirling for bill dated 13 Feburary 1730 payable on demand….

By James Lockart, indweller burgess of Stirling for bill 10 July 1730 payable 15 of month

By William Morison in Denny for two bolls of malt received 21 June 1742 for…

By Alexander … Junior of …for bill 25 April 1737 payable ten days after date

By John Rowat parish of Breichyle at Kilsyth as remains of a bill

By John Jarvey tenant in B…for bill 28 June 1730 payable on demand.

By John Graeme of Cairnoch, Merchant in Glasgow for bill 21 November 1730 payable 10 days after dates.

By Malcolm Murray of Marchfield for bill 13 April 1723 payable 15 May …

By Donald Robertson Drover in Glenbuckie for bill 6 January 1710 payable the first of February

By James Stewart parish of Innernety and Donald D Stewart ee Connel and Sealy for bill 24 May 1723 payable September

By John Buchanan at D…of… for bill 10 September 1730 payable on demand

By James Stewart younger? Of Gartnafuaran for bill 17 December 1718 payable 1719

By John McLaren parish of Deravenock in Killin parish for bill of 1720 payable 10 March

By Lieutenant James Graeme of the British … and …Graeme of Badavon Connly and Seallie for bill 24 June 1715 payable on sight

By Eneas (Angus) McDonald at Lawers for bill 24 April 1729 payable 29 September said year

By William Monro of Allas (/.) for bill 12 April 1729 payable 20 May year after

By John Stewart of Hyndfield and John McInlay pardioner [portioner?] of Muirlagan Connlly & Seally for bill 6 April 1727 payable on demand

By Donald Stewart Drover in Glenfinglas and John Stewart son to Alex? Stewart in Drunky Connlly and Seally 1 March …

By Duncan Stewart, Servant to the Laird of Apine…for bill …1715 payable 22October year after

By William Stewart, brother to Ardvorlich for bill payable first September 1716

By Alexander …(Dun) Stewart in Milntown of Strathgar? For bil 20 November 1714 payable at land 1715

By Robert Batison at Port of Menteith for bill 10 September 1739 payable 22 …year

By John Campbell in Boghall

By James Drummond, Tacksman of Corry..reick for bill dated the 10 November 1735 payable 15 November 1736

By John McArthur in Portnellan of Apine for bill the 15 February 1715 payable on demand

By William Buchanan in Ballachallan and George Buchanan in Gart Connlly and Seally for bill the 17 December 1733 payable 22 …1734

By John McArthur at Kirk of Callander and John McKr… in Coldhamee Connly and Seally for bill of November 1734 payable at Whitsunday 1735

By Alex Buchanan of Dullater at Mochaster for bill 2 December 1735 …

By David Stewart in Glenfinglas for bill 11 September 1739 payable 22nd 1739.

By John Craig of Cull for bill 20 June 1733 pay at Mar

By Duncan Graeme in Gartmalllian of Monteith for bill 25 December 172? Payable the last day of month …. resting by Thomas Graeme in…

By Robert Stewart of Culliemoir for bill 15 Sept 1725 payable by 22 October year after

By Colin Buchanan of Auchingyle of bill 27 November1723 payable the December year after

Ditto rests a guinea as marked on the back of Do bill

By John Glass of Sauchie bill of July 1742 payable by November said year

By John Glass in Abey …1739 payable eight days after date.

Nu Malcom McGibbon Maltman in Stirling for bill ….

By James Alexander son to Archibald Alexander Flesher in Glasgow for bill …..29 of month

By Robert Buchanan at… of Craigforth for bill…

By Robert Randall…at Thornhill for bill 15 August 1735 payable in days after date.

By Thomas McLauchlan flesher in Stirling place, 10 May 1731 payable the first of July year after.

By James McArthur carter at St Ninians and Colin McArthur Smith at …in June 1734 payable the fifteenth of month

By Robert Stirling, dyster at Stirling Bridge for bill March 1729 payable 10 days after date to Robert Thompson of …to the defunct

By James Davie Milner in Goldenhoowe miln for bill 19 August 1724 payable …

By Alexander Hall, Carter in Neither Bobburn for bill 19 Apirl 1735 28th said month

By David Bryson? Lieutenant in the Fusiliers for bill payable to David Cunningham, merchant in Edinburgh on account of the defunct which was …by him and is …1719..

By James Chalmers, junior Carter? In Stirling for bill 2 September 1721 payable the first of November year after

By Thomas Morison writer in Falkirk for bill 30th March 1720 payable on demand.

By Alexander McFarland in Auchary for bill 13 February 1734 payable on first of May year after

By Patrick? Stewart in Callibohally (Calziebohalzie) …Donald McKinlay younger for bill 16 October 1740 payable at…

By John Stewart nephew to the Laird Annat for bill 26 April 1734 payable on demand

By William Hart, tenant in Burn of Glassingall as remainds of a bill dated 21 November 1737 payable…

By Matthew Stirling in Gateside of Glassingall for bill 7 January 1742 payable….

By Michael Stirling in Kairnston (Cairnston) of Glassingall for bill …

By Lilias Murray, Relict of William Wright Maltman in Stirling for bills 21 March 1737 payable …days after

By William… …in Nether BoBurn for bill 7 April 1740 payable Whitt yearafter

By …Ronald Weaver at St Ninians for …bill to the defunct dated 2 November 1738 payable 20 December

By John Gillespie at Parkneuck of bill 28 December 1739 payable on demand

By John Jarvey tenant in Bents and Bailie Jarvey his son for bill 19 July 1742 payable at Mar…

By James Graeme of Correiclet, Alexander Graeme his brother and James Graeme late MacGregor tenant….for Conlly and Seally dated 6 April 1725

By William McKilligan parish of Stachristock of…1740

By John Waters parish of Cairnoch for bill ….by the William McKillian to the defunct 13 September 1732 payable the first October said year

By John Allan in Broatyet of Denny for bill drawn by Donald McKillican …dated 6 January 1730 payable at…. Remains…

By James Buchanan in …bill dated 2 August 1736 payable 10 days after date

By Robert Murray Dyster in Cambusbarron for fait a compli 4 June 1730

By James Buchanan Dyster in Glasgow for bill 13 July 1731 payable 20th of month

By James Campbell brother to Glenlyon for bond 20 November 1717 payable at Lambas 1710 Regt in the books of Session …

By John Dickson merchant in Kelso for bill drawn by James Polls? Payable to the defunct dated the 20th June 1720 payable at Lambas …

By James Graeme of Braco for bill 24 August 1725 payable at Whit[Sunday] 1726

By Donald? For 1 dozen strong claret with boules furnish first September 1725

By Mary Campbell in Gogar for bill 4 July 1732 payable the September 1732 ….

Y the Honourable Mr Charles Johnston …23rd June 1742

By William Graeme of Drunkie for …wine paid

By Janet Rob…of Wester Grays?…furnished to her husbands funerals

By John Nairn of Greenyards…

By David Drummond of Pillkilling? Paid with a draught upon John Breadie …Muthill the eight June 1711?

By Sir Alexander …of Keip…

By Janet D… relict of Murdoch McKillican for …before the …3 June 1729

By…Boswell…

By the proprietors of Carnoch of Plean …and by for Mich Bruce of Glenahyle for …

By the deceased David Graeme of Orchil? Place

By the Right Honourable the Lord Elphinstone (or Johnston) for Mr Archibald Napier Minister of the Gospel at Kilmadock.

By Donald Napier for tartan and muslin ?

By Colin Campbell brother to Sir James Campbell of Aberuchil for …

By Patrick Edmonston? Of New Cams (Newton Cambus) for state a…Mrs Stewart the 9th July 17…

Item Robert Stewart Baillies in Dine… for Bill dated 20th June 1715 payable 15 July year after

Item These was in the defunct custody time of his death…and… to the extent of six hundred pounds Scots.

These was forty bolls of bear ins ti…which was sold at six founds Scots …to Alexander Abercromby merchant in Alloa

Item There was in the defuncts …thirty bolls of malt, which at ten marks a boll, …the current price at the time.

There was a …that belonged to the defunct. Sold at six pounds sterling.

There was three cows sold at six pounds ten shillings sterling.

By George Drummond of Blair Drummond, £46, 14,4 as his …duty croft 1740 to which the defunct had sought as factor for the earl of Rothes

Item there was …the defunct by John Edmonstone of Cambus Wallace and Alexander Stewart of Annat ber… dated 14 March 1741 payable.

Item the said John Edmonstone as the remaining of a bill dated …. May 1742 …

Item by John Bruce in Keir and John Morison in Woodend of Ballachallan per bill dated the 2nd June 1742 Conlly and Seally…

Item by Robert McLaren in Letter and John Stewart in Cambusbeg per bill dated

Item by Duncan and John Stewarts in Berryhill per bill dated

Item by the Alexander Stewart of Annat per bill. Dated …1740 payable at Mar…1741

Item by John McArthur in Buchany per bill dated

Item by Dougal McGregor Servant to Robert Stewart in Annat per bill dated

Of George Monro Esquire Commissary of the Commissariat of Stirling Hereby …approve and confirm the Testament …and Inventory of …Alexander Stewart writer of Stirling of the date the twenty … Of October 1743 and also confirm Archibald Stewart the Defuncts only son sole executor of the defunct as therein mentioned, and to the Debts and sums of money following were …the defunct at his death and is …in the Inventory of the Confirmed testament aforesaid …fifty pounds Scots …and bygone interest…thereof contained in a bill …by Robert Christie Maltman in Stirling upon and accepted by John Thompson at Whinwell dated the tenth date of February 1722, …at this …for a not payment and the protest …in the commissary …books of Stirling upon the tenth day of September said year. Item the sum of …three pounds Scots…and bygone~…rests therefores…in another bill drawn by the said Robert Christie….upon and accepted by the said John Thompson for dated the said tenth of February 1722, also …to the Defunct at his …for not payment and the …in the Town Court Books of Stirling the 11th day of May 1723 upon both which… the Defunct raised letters of …against the said John Thompson as the …and grant full pardon to the said Archibald Stewart to uplift…and discharge and of need be call and …for said sums, and …every other thing else…The said Archibald Stewart having found William Shaw merchant in Stirling that the same be made forthcoming to all partners …interest therein as…whereof these presents are given and …at Stirling the twenty day of January 1755 years…

Children

Alexander Stewart, 1st of Glassingall, and his wife, Helen Fleetwood, had the following children:

1. Hellen Stewart, b. Abt 15 Dec 1717, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Hellen Stewart, b. Abt 15 Dec 1717, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

According to the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), Hellen “died unmarried.”

2. Jean Stewart, b. Abt 14 Jun 1719, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Jean Stewart, b. Abt 14 Jun 1719, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

Jean’s information is presented below.

3. John Stewart, b. Abt 21 Aug 1720, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. Bef 1742, Glassingall, Dunblane, Perthshire, Scotland (Age ~ 21 years)

John Stewart, b. Abt 21 Aug 1720, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. Bef 1742, Glassingall, Dunblane, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. Bef 1742, Glassingall, Dunblane, Perthshire, Scotland  (Age ~ 21 years).

(Age ~ 21 years).

According to the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), he “died unmarried.” As his brother, Archibald is listed as their father’s only son at the time of their father’s death in 1742, then John must have died before then.

4. Anna Stewart, b. Abt 14 Jan 1722, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Anna Stewart, b. Abt 14 Jan 1722, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

According to the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), she “died unmarried.”

5. Isobell Stewart, b. Abt 25 Apr 1723, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Isobell Stewart, b. Abt 25 Apr 1723, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

According to the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), she “died unmarried.”

6. Margaret Stewart, b. Abt 12 Apr 1724, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Margaret Stewart, b. Abt 12 Apr 1724, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

According to the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), she “died unmarried.”

7. Catharine Stewart, b. Abt 12 Oct 1726, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Catharine Stewart, b. Abt 12 Oct 1726, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN

, d. UNKNOWN

According to the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), she “died unmarried.”

8. Archibald Stewart, 2nd of Glasingall, b. Abt 26 Nov 1727, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Archibald Stewart, 2nd of Glasingall, b. Abt 26 Nov 1727, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

Archibald succeeded his father in the estate of Glassingall. He never married and had no children. He was succeeded in the estate by his nephew, Alexander Jaffrey.

According to Ailsa Gray of Glassingall (2022), Archibald, like his father, became a maltman in Stirling and was still working as one around 1756. There’s a reference in the guildry books to him paying some stipend due to Stewart of Annat and that stipend remained outstanding. He was an ardent Jacobite and was defence witness at the trial of James Stewart of The Glen accused in the Appin Murder (though he never actually testified). No will or death certificate has been located for him.

Archibald is recorded in the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856) as “Archibald Stewart, an only son, took up the succession of these properties as heir to his father. He destined the estates to his nephew, Alexander Jaffery, only son of his sister, Janet Stewart, He died unmarried.”

Jean (Janet) Stewart and John Jaffrey, Provost of Stirling

Jean Stewart, b. Abt 14 Jun 1719, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN. Jean was the second daughter of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Glassingall, shown above.

, d. UNKNOWN. Jean was the second daughter of Alexander Stewart, 1st of Glassingall, shown above.

Jean married on 30 Mar 1739 in Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  to John Jaffrey, b. 21 Aug 1720, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland

to John Jaffrey, b. 21 Aug 1720, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN. He had been previously married and had children from his first marriage.

, d. UNKNOWN. He had been previously married and had children from his first marriage.

Jean’s birth record gives her name as “Jean.” She is recorded in the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856) as “Janet Stewart, who was the second wife of John Jaffrey, by which marriage she had issue as under (Helen Jaffery…), (Alexander Jaffery…), other children who died unmarried.”

Jean’s husband, John Jaffrey, served initially as Baillie and later as Provost of the town of Stirling (Alexander Barty, The History of Dunblane) and is alleged to have opened the town gates to Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1745 at the behest of Jean. Her family was deeply involved in the 1745 Rising.

When Jean’s youngest brother, Archibald Stewart, 2nd of Glassingall, died without children, the next closest heir to the estate of Glassingall was Jean’s son, Alexander Jaffrey, who became 3rd of Glassingall.

Marriage and Children

John Jaffrey had three children from a previous marriage to Jean Russell, namely: Henry, John and Jean. Their information is beyond the scope of this research project, other than to note that Henry Jaffrey had three grandchildren who were claimants in the Glassingall ultimus haeres hearings. John Jaffrey and Jean Stewart had the following children:

1. Helen Jaffrey, Heiress of Glasingall, b. 3 Feb 1740, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Helen Jaffrey, Heiress of Glassingall, b. 3 Feb 1740, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

Helen Jaffrey’s information is presented below.

2. Anna Jaffrey, b. Abt 1743, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Anna Jaffrey, b. Abt 1743, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

Nothing more is known of her.

3. Alexander Jaffrey, 3rd of Glassingall, b. Abt 1750, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Alexander Jaffrey, 3rd of Glassingall, b. Abt 1750, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

Alexander’s uncle, Archibald Stewart, 2nd of Glassingall, died without children. Alexander was his closest heir to inherit the estate of Glassingall. Alexander, himself, had no children, and the estate passed to his nephews, Thomas and Alexander Smith.

Alexander is shown in the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856) as “Alexander Jaffrey, only son, who, under the deed executed by his uncle, Archibald Stewart, completed his title to these properties. He again gratuitously conveyed these to his sister’s sons, Thomas and Alexr Smith. He died unmarried.”

4. Other Children Jaffrey

Other Children Jaffrey, b. UNKNOWN in Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN.

According to the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), John Jaffrey and Jean Stewart had additional children whose names are not listed and who died unmarried.

Helen Jaffrey, Heiress of Glassingall, and Thomas Smith, Sr.

Helen Jaffrey, Heiress of Glassingall, b. 3 Feb 1740, Stirling, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN. Helen was the eldest daughter of Jean (Janet) Stewart and John Jaffrey, Provost of Stirling, shown above.

, d. UNKNOWN. Helen was the eldest daughter of Jean (Janet) Stewart and John Jaffrey, Provost of Stirling, shown above.

Helen married on 12 Jul 1761 in Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland  to Thomas Smith, b. Abt 1740, Scotland

to Thomas Smith, b. Abt 1740, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

Helen is mentioned in the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856) as “Helen Jaffrey, born 3 Feb 1740, married Thomas Smith, Sr. of Edinburgh, and had issue as follows….” Nothing more is known about Thomas Smith.

Upon the death of Helen’s younger brother, Alexander Jaffrey, 3rd of Glassingall, without children, the estate of Glassingall passed to Helen’s sons Thomas and Alexnader Smith.

Children

Helen Jaffrey and Thomas Smith, Sr., had the following children:

1. Other Children Smith, b. Between 1762 and 1775, Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland, d. UNKNOWN

Other Children Smith, b. Between 1762 and 1775, Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland  , d. UNKNOWN.

, d. UNKNOWN.

According to the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), Thomas Smith and Helen Jeffrey had other children who died young.

2. Thomas Smith, Jr., b. Abt 1765, Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland, d. 1829, Cuba (Age ~ 64 years)

Thomas Smith, Jr., b. Abt 1765, Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland  , d. 1829, Cuba

, d. 1829, Cuba  (Age ~ 64 years).

(Age ~ 64 years).

Thomas Jr.’s birth record has not been identified. He was the eldest son of Thomas Smith, Sr. and Helen Jaffrey, Heiress of Glassingall. As the eldest son, he should have inherited Glassingall from his mother, however the estate went to his younger brother, Alexander, instead. Allegedly, Thomas and Alexander fell in love with the same woman and struck a deal whereby Thomas relinquished his rightful interest in the estate of Glassingall in exchange for Alexander withdrawing his love-interest in the woman. Her name is lost to history. Their alleged real-life love-triangle provided some of the inspiration for author Robert Louis Stevenson for the story in his novels, Kidnapped and Catriona, in which Thomas Smith, Jr. is portrayed as the deceased character of Alexander Balfour of Shaws, father to the central character of Davie Balfour. The fictional estate of Shaws is based on the real-life estate of Glassingall.

Thomas Smith, Jr. was one of the founders of the Canada Company with John Galt and other investors in Canada and the UK. It was established to acquire and develop Upper Canada’s undeveloped clergy reserve and Crown reserve lands and to redistribute them to immigrant settlers at a profit to the company. Galt was the original superintendant, but quickly found himself in trouble. When Galt was accused of gross mismanagement in 1829, Thomas Smith was sent to Canada to review Galt’s books and business practices. This resulted in Galt’s dismissal from the company. Smith also uncovered disreputable investment practices on the part of several Canadian investors who were among a group of powerful elites known collectively known as “The Family Compact.” Upon discovering these illegalities, Smith found himself on the wrong side of power and was fired.

After losing his job with the Canada Company, he travelled to the USA and later to Cuba where he is believed to have died in a shipwreck offshore on route to India in 1829.

He fathered an illegitimate son, Thomas Stuart Smith who went on to become a respected painter and founder of the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum in Stirling, Scotland.

Thomas is mentioned in the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), as “Thomas Smith, who previous to leaving for India on his passage to which he died unmarried, conveyed his joint interest to his brother, Alexander.”

Thomas Smith, Jr., had relations with an unknown woman with whom he had the following illegitimate son:

1. Thomas Stuart Smith, b. 1815, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. 1869, Avignon, France

, d. 1869, Avignon, France  (Age 54 years).

(Age 54 years).

Information on Thomas Stuart Smith is presented below.

3. Alexander Smith, 4th of Glassingall, b. 4 Feb 1770, Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland, d. Abt 1848, Glassingall, Dunblane, Perthshire, Scotland (Age 77 years)

Alexander Smith, 4th of Glassingall, b. 4 Feb 1770, Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland  , d. Abt 1848, Glassingall, Dunblane, Perthshire, Scotland

, d. Abt 1848, Glassingall, Dunblane, Perthshire, Scotland  (Age 77 years).

(Age 77 years).

Alexander was the younger son of Thomas Smith and Helen Jaffrey, Heiress of Glassingall. As the younger son, the estate of Glassingall should have passed to his older brother, Thomas. However the estate went to Alexander instead. Allegedly, Thomas and Alexander fell in love with the same woman and struck a deal whereby Thomas gave up his rightful interest in the estate of Glassingall in exchange for Alexander withdrawing his love interest in the woman. Her name is lost to history. Their alleged real-life love triangle provided some of the inspiration for author Robert Louis Stevenson for the story in his novels, Kidnapped and Catriona, in which Alexander is portrayed very unflatteringly as the villanous and miserly character of Ebenezer Balfour of Shaws. The fictional estate of Shaws is based on the real life estate of Glassingall.

Alexander also owned a townhouse, called Glassingall House, at 30 Bow Street in the town of Stirling.

Alexander has not been identified in the 1841 census

Alexander died intestate and without children in 1849 so the estate of Glassingall reverted to the Crown. 18 people laid claim to the estate, most of whom were distant relatives from among various descendant branches of the Stewarts of Annat. The ultimus haeres hearings lasted from 1849-1856. Ultimately, the court found in favour of his illegitamite nephew, Thomas Stuart Smith, whose real-life persona provided the inspiration for the central character of Davie Balfour in Kidnapped and Catriona.

Thomas Smith, Jr.

Thomas Smith, Jr., b. Abt 1765, Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland  , d. 1829, Cuba

, d. 1829, Cuba  (Age ~ 64 years).

(Age ~ 64 years).

Thomas Jr.’s birth record has not been identified. He was the eldest son of Thomas Smith, Sr. and Helen Jaffrey, Heiress of Glassingall. As the eldest son, he should have inherited Glassingall from his mother, however the estate went to his younger brother, Alexander, instead. Allegedly, Thomas and Alexander fell in love with the same woman and struck a deal whereby Thomas relinquished his rightful interest in the estate of Glassingall in exchange for Alexander withdrawing his love-interest in the woman. Her name is lost to history. Their alleged real-life love-triangle provided some of the inspiration for author Robert Louis Stevenson for the story in his novels, Kidnapped and Catriona, in which Thomas Smith, Jr. is portrayed as the deceased character of Alexander Balfour of Shaws, father to the central character of Davie Balfour. The fictional estate of Shaws is based on the real-life estate of Glassingall.

Thomas Smith, Jr. was one of the founders of the Canada Company with John Galt and other investors in Canada and the UK. It was established to acquire and develop Upper Canada’s undeveloped clergy reserve and Crown reserve lands and to redistribute them to immigrant settlers at a profit to the company. Galt was the original superintendant, but quickly found himself in trouble. When Galt was accused of gross mismanagement in 1829, Thomas Smith was sent to Canada to review Galt’s books and business practices. This resulted in Galt’s dismissal from the company. Smith also uncovered disreputable investment practices on the part of several Canadian investors who were among a group of powerful elites known collectively known as “The Family Compact.” Upon discovering these illegalities, Smith found himself on the wrong side of power and was fired.

After losing his job with the Canada Company, he travelled to the USA and later to Cuba where he is believed to have died in a shipwreck offshore on route to India in 1829.

He fathered an illegitimate son, Thomas Stuart Smith who went on to become a respected painter and founder of the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum in Stirling, Scotland.

Thomas is mentioned in the Glassingall Court of Session Papers (1849-1856), as “Thomas Smith, who previous to leaving for India on his passage to which he died unmarried, conveyed his joint interest to his brother, Alexander.”

Thomas Smith, Jr., had relations with an unknown woman with whom he had the following illegitimate son:

1. Thomas Stuart Smith, b. 1815, Stirlingshire, Scotland , d. 1869, Avignon, France (Age 54 years).

Thomas Stuart Smith, b. 1815, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. 1869, Avignon, France

, d. 1869, Avignon, France  (Age 54 years).

(Age 54 years).

Information on Thomas Stuart Smith is presented below.

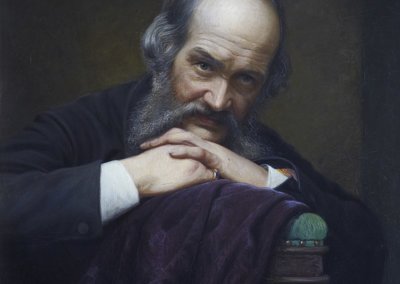

Thomas Stuart Smith, artist

Inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s fictional character of Davie Balfour of Shaws in the novels, Kidnapped and Catriona

Thomas Stuart Smith, b. 1815, Stirlingshire, Scotland  , d. 1869, Avignon, France

, d. 1869, Avignon, France  (Age 54 years). Thomas Stuart Smith was the only child of Thomas Smith, Jr. and his unknown lover, shown above. Thomas was illegitimate.

(Age 54 years). Thomas Stuart Smith was the only child of Thomas Smith, Jr. and his unknown lover, shown above. Thomas was illegitimate.

Thomas Stuart Smith was a Scottish painter whose colourful life story provided the inspiration for the fictional character of Davie Balfour of Shaws in Robert Louis Stevenson‘s novels, Kidnapped and Catriona. He was the illegitimate son of Thomas Smith, whose brother, Alexander Smith, was the last in the Stewart line to own the estate of Glassingall. When Alexander died intestate, Thomas Stuart Smith, was ultimately the successful of 18 claimants vying for the inheritance of the estate. He later sold Glassingall and used the money to support his art and to later establish the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum in Stirling, Scotland. His paintings were significant for the era in portraying black persons as free and independent people during a time when slavery and abolition were hotly contested issues.

Source: Wikipedia

Life

Thomas Stuart Smith was born in 1815 as the secret illegitimate nephew of Alexander Smith, who had the estate at Glassingall, Dunblane, Scotland. Alexander’s brother, the father, sent Thomas to a school in France whilst he conducted his business in Canada and the East Indies. In 1831 no fees were paid and Thomas thought his father must have died. He returned to England, when he and his uncle learned of each other for the first time. They did not meet, but Alexander advanced sums to him from time to time.

Smith started working as a tutor. He later became interested in painting from an Italian master painter whom he met whilst serving as a traveling tutor to a British family. His uncle Alexander supplied funding so that he could travel and paint in Italy starting in 1840.

By the end of that decade, Smith was having his work accepted by both the Salon des Beaux Arts in Paris and the Royal Academy in London. His first painting at the Royal Academy was bought by Professor Owen, an acquaintance of Edwin Landseer, who was said to have admired it repeatedly.

Inheritance

In 1849 Alexander Smith died intestate. Thomas took possession of the family’s estate in 1857 after vying at great expense with eighteen other aspirants. During the eight years that he had waited in hope of his inheritance, he taught art at the Nottingham School of Design. James Orrock, the collecter and watercoulourist, was one of his pupils; he commented on how Smith could paint anything. Smith was known to the Barbizon School of realistic painting, including the animal painters Constant Troyon and John Phillip RA.

Having gained the estate, he kept it just six years. He sold it and used the funds to move to London. His legal costs had been high. His new fortune enabled him to create an art collection at a studio in Fitzroy Square that included his own work. He decided to create an Institute in Stirling to house his new collection. He drew up plans for a library, museum, and a reading room and he offered £5,000 to the council if they could donate a site within two years. He signed the trust into existence in November 1869 with himself, James Barty, the Provost of Stirling and A.W.Cox, a fellow artist, as trustees. He did not see his plans fulfilled as he died the next month in Avignon.

Legacy

Smith is known primarily for founding the Smith Institute, which is now called the Stirling Smith Museum and Art Gallery. Smith also has hundreds of paintings in public ownership.

Two of Smith’s works that are still thought to be important are portraits he painted of black men. Unlike other depictions at the time, in which black people were included as servants, Smith’s portraits Fellah of Kinneh and The Pipe of Freedom show his subjects as independent and free; they were painted to celebrate the abolition of slavery in America in 1865 following the American Civil War. He also did a smaller painting called The Cuban Cigarette, which has a similar presence. The Pipe of Freedom shows a man lighting a pipe; behind him a slave sale notice has been partially covered by an abolition notice.

Source: Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum

Thomas Stuart Smith was a man of fluctuating fortune with a colourful history who became an artist of considerable accomplishment, widely admired by his fellow artists. His grandmother was one of the Jaffray family in Stirling. The family story was that Thomas’s father and uncle were in love with the same woman, had a disagreement over her and parted. Thomas was illegitimate and his mother died when he was young. His father, a merchant working in Canada and the West Indies, sent the young Thomas to school in France. When the school fees failed to arrive in 1831, Thomas deduced that his father was dead. Thomas and his uncle Alexander Smith who held the estate of Glassingall, Dunblane were shocked to hear of each other’s existence. Alexander Smith, although he never met his newly discovered nephew, provided some financial support for him from time to time.

Thomas Stuart Smith obtained a post as a tutor to a young noble man, travelling with the family to Naples, where he obtained for himself some tuition in painting from a master painter “Marsigli, the first painter here and one of the first in Italy”. In 1840 Thomas made “my first attempt at landscape and my first oil picture”. He was funded by his uncle to study and paint in various places in Italy in the 1840s, and by 1849 was exhibiting both at the Salon des Beaux Arts in Paris and the Royal Academy in London.

In that year, Alexander Smith died leaving no direct family and no will. Although he had been Thomas Stuart Smith’s main financial support, there was difficulty in proving their relationship, and eighteen people pursued claims on the Glassingall estate. It took Smith from 1849 to January 1857 to secure the inheritance of Glassingall.

The estate was much diminished through the demands of legal fees, and Smith missed the warmth and light of the continent. In 1863 he sold the estate, rented a studio at Fitzroy Square in London and began to build up his own art collection, purchasing from his contemporaries both in Britain and in Europe. With no need to sell his own work, he liked the idea of building an Institute which would house it and his general collection for ‘the welfare of the town and district of Stirling in Scotland’. He drew up a ‘Trust Disposition and Settlement’ for the building of a ‘Museum or Institute’ in Stirling, agreeing to provide £5000 for the building if the town provided a site for it within two years. He had a very specific idea of how the building should be composed of three principal rooms of offices and store rooms, with space left on either side for contingent additions. The style of the building to be plain (Italian), but of first-rate material and construction – the three rooms to be a Museum, a Picture Gallery and a Library and Reading Room, adapted for the benefit of the artisan and working classes.

He intended to oversee the construction himself. The Trust Disposition, naming his fellow artist A. W. Cox, his solicitor James Barty and the Provost of Stirling as Trustees was signed in November 1869. On 31 December he died unexpectedly at Avignon in the south of France.

T. S. Smith was something of an artist’s artist. Having had to struggle to study and practice his art, he had great sympathy for others in the same position,and frequently helped others. The first picture he exhibited in the Royal Academy was a painting of two young artists asking for shelter at the door of a convent in Italy. It was bought by Professor Owen, who had it hanging in his London house. According to Sir William Stirling Maxwell, ‘The late Sir Edwin Landseer was struck by it and never visited Professor Owen without taking it down from the wall and examining it with some new expression at the masterly qualities which it exhibited.’

Smith was accomplished in landscape, interiors and excelled in portrait painting too. Whilst pursuing his claim to the Glassingall estate, he lived as an art teacher and portrait painter in Nottingham for a time. One of his pupils, James Orrock (1829-1913) recalled his work with delight and remembered him as ‘a man who could paint anything’, who was a close friend of John Phillip RA, and who knew Troyon and most of the other masters of the Barbizon School. Phillip regarded Smith as ‘one of the best living colourists’.

In the last year of his life, Smith submitted two remarkable portraits to the Royal Academy. Both were of black men of African origin. The Fellah of Kinneh depicts a young man in striped robes. The Pipe of Freedom celebrates the abolition of slavery in America. A smaller study of the same man, The Cuban Cigarette, shows the subject in profile. In subject and presentation, these portraits are quite rare in Scottish painting, and were given pride of place in the Africa in Scotland exhibition in Edinburgh in 1996. They also featured in the Black Victorians exhibition in Birmingham in 2005 and in Manchester in 2006. Black people were sometimes included in paintings. The Lost Child Restored by Sir George Harvey in the Smith’s own collection, where the negro servant is depicted in the doorway is a good example of an incidental inclusion. In Smith’s paintings of black men, the subjects are central, handsome, proud, independent and free. With fellow landowners in the Stirling area managing estates in Jamaica, such paintings would not have been popular. However, another member of the Jaffray family, ‘Citizen’ William Jaffray (1749-1828) had attained local fame through assisting a female slave on the way back to the West Indies to abscond and claim her freedom. His national fame was won through vaccinating some 16,000 children and saving Stirling from the small pox epidemics which raged elsewhere.

The work of T. S. Smith is often overlooked or under valued in Scottish art history. This is because the history is largely market-related. Smith had no need to paint for the board room or the market; his paintings were garnered for Stirling. He wanted his paintings to survive in a single collection, and bought back earlier works for that purpose when he was able to do so.